While Canadian organic potato growers are seeing increased demand, there’s still a lot of issues to contend with in the industry.

At Kroeker Farms in southern Manitoba they’ve been growing potatoes for decades, but in the early 2000s they noticed interest in spuds was starting to dip. Fad low carb diets like Atkins had people shying away from eating potatoes.

Wayne Rempel had just become CEO of the potato farm and started looking for new opportunities for their spuds.

“Some of the younger people in our company and some of our shareholders said, ‘Hey, why don’t you do organic?’ And so, we started an organic production — our first year was 2002,” he says in a phone interview.

At the start they converted their poorest fields to organic production. With the three years it takes to transition to organics and gain certification, they didn’t want to risk losing out on any production with their better fields.

“In essence, our first many years of organic conversion and production of potatoes was on our poor soil. Since then, we’ve changed our mentality and now we pick some of the best soils to grow organics on,” Rempel explains.

Organic potato production worked well for them with the farm now growing over 1,000 acres of organic potatoes annually — making them one of the largest organic potato farms in the country. They still grow conventional fresh potatoes as well.

Martien Hakkers also came from a long line of potato growers. His family immigrated to Newtown Cross, P.E.I. in 1988 from Holland, establishing a potato farm there. As Martien eventually started to take over the farm from his father, Peter, he decided he wanted to do things differently.

“I was just tired of dealing with all the chemicals. And at the time we were using Thimet, which was an insecticide for wireworm. And you couldn’t even get around without it, like the smell of it alone could kind of turn your stomach,” he explains in a phone interview.

In 2015, Martien started to switch the farm over to organic potato production — it took them five years to fully get out of conventional potato production. They now grow 400 acres of organic spuds.

“It’s been really good. It took us a while to kind of get market share, but it’s been really nice growth for the farm. And it’s been nice to see some returns,” Martien says.

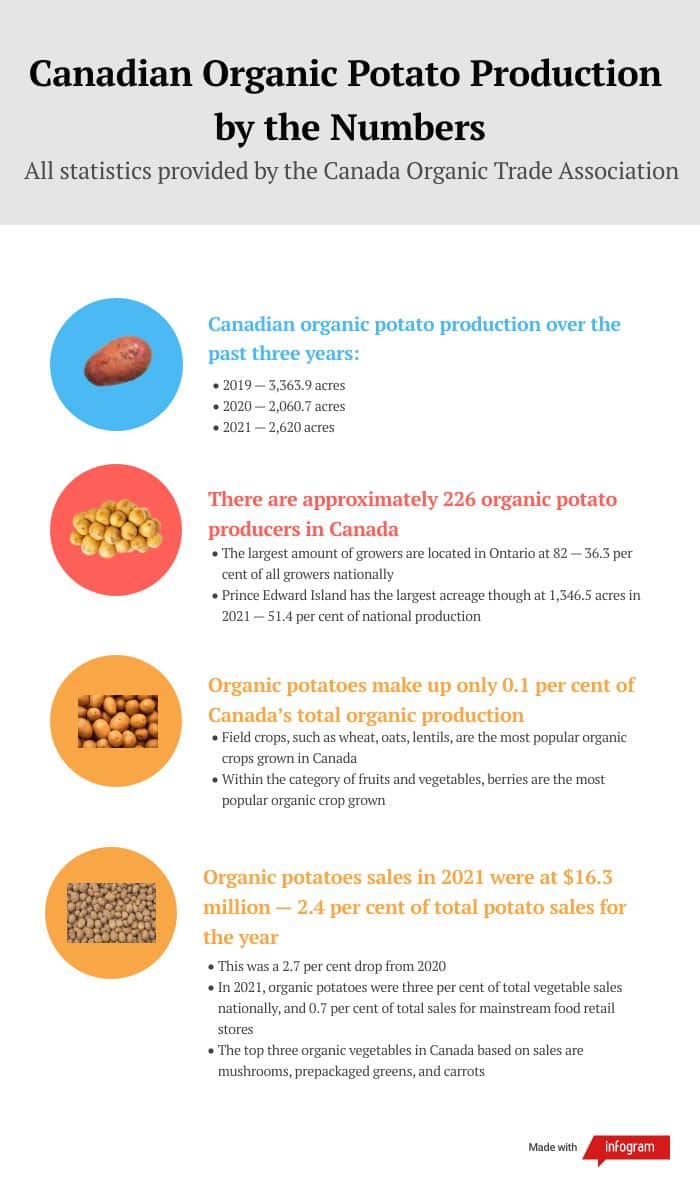

Kroeker Farms and Hakkers Organics are part of a growing industry across Canada. With 226 organic potato growers across Canada, according to statistics from the Canada Organic Trade Association (COTA), those working in the industry see opportunity there. But organic production isn’t easy, and regulations are holding back some areas of the industry.

Canadian Organic Crop Regulations

In Canada there are two jurisdictions for organic regulations — provincial and national. Both are subject to the Safe Food for Canadians Regulation, which is overseen by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). If you export your products outside of your province nationally or internationally, then you fall under the national regulations which are run by the CFIA. If you sell locally within your province and there is provincial regulations, then you’re governed by provincial regulations. You must also follow the federal truth in advertising regulations

To sell nationally and internationally you must be a certified organic producer under the Canada Organic Regulations (COR) regulated through the CFIA. The CFIA oversees verification officers who will check what inputs you are using and if your growing practices are in compliance with Canadian Organic Standards. There’s a list of inputs under the Canadian Organic Standards that states what is allowed to be used for fertilization and pest/disease control. By receiving an organic certificate, it means your organic production has followed all regulations under the Canada Organic Regime. Annual inspections are mandatory.

“When you sell your produce, your product to your client, you usually send also the organic certificate that is the proof that the organic designation is real, it can be trusted,” Nicole Boudreau, a coordinator with the Organic Federation of Canada, explains in a phone interview.

To become an organic grower in Canada you must go through a transition period, which takes three years. The land that you use cannot have synthetic pesticides or any other prohibited substances used on it for three years before organic crops are able to be grown on it. During these three years growers start using organic practices but still sell the crops produced on them in the conventional marketplace.

For Canadian growers to be able to export their products internationally, Canada has organic equivalency arrangements signed with the United States, European Union, Japan, Costa Rica, Taiwan, the United Kingdom and Switzerland. The equivalency arrangements allow for products labelled as organic and produced in Canada to be sold in these countries with the organic label as well, with organic products from these countries also able to be sold in Canada under the organic label.

Canada doesn’t have equivalency agreements with every country though. For example, if Canadian growers want to sell organic products to China, they must know what the organic import regulations are for China and then follow those rules.

Growing Potatoes the Organic Way

Organic potato production is focused on being preventative in your pest and disease control, while conventional production is focused on being reactive to crop threats.

“We had to change the way we thought. This whole paradigm shift in production is that our focus is 100 per cent on healthy soil. So, the soil is healthy, lots of the right balance, lots of organic matter and just generally very healthy, then the potatoes don’t need as many pesticides,” Rempel says.

To keep that soil healthy, organic growers’ focus on crop rotations. At Kroeker Farms they do a three-year rotation, growing a vegetable crop of potatoes or onions, then hemp, beans, wheat or corn; with the third year being a restoration year where they do plow downs to get the crop ready for vegetable production.

At Hakkers Organics they also do a three-year rotation, but they are fully focused on enhancing their potato production. In non-potato years they grow mustard, buckwheat, and seed radish, for green manure crops. None of these crops are sold commercially with them all getting plowed down.

“Everything we do is to control wireworm. And we’re seeing after about five years of buckwheat mustard, that’s when we really start to see a decline. It’s not like a one- or two-year solution. So that’s our number one pest issue in organics,” Martien explains.

Organic potato production does require closer management than conventional. Fields are monitored more regularly both Rempel and Martien say. Martien adds that field checks are paramount at certain times of year such as when Colorado potato beetles lay their eggs.

“We spend a lot more time scouting the fields. But we’ve generally had good luck. We’ve had very little disease pressure and generally good quality potatoes,” Martien says.

Any products used must be natural and from the approved CFIA list. According to Rempel there are some natural products which aren’t on the CFIA list. For example, garlic oil can’t be used to help keep potatoes from sprouting. The CFIA doesn’t allow for any food products to be used for organic crop control, however there are changes underway for this to be allowed in the future.

“They are very, very restrictive. And that’s probably one of our biggest challenges in our organic production,” Rempel adds.

Both farms have found that by following organic production methods, they’re able to grow organic potatoes that have comparable yields to conventionally grown spuds.

“Quality is just as good as conventional and certainly needs to be just as good. We thought, at first, when the consumer would buy organic potatoes, they would realize, ‘Okay, we’re buying organic, and so the quality doesn’t have to be as good.’ What we discovered is that when somebody pays a premium for something, they want a premium product, and so the quality of the potatoes has to be top notch,” Rempel explains.

Not So Organic Seed Potatoes

While regulations are strict around how certified organic fresh potatoes can be grown, rules aren’t as strict about the seed that’s planted to grow those crops. Conventional potato seed can be planted for organic potato production.

Both Hakkers Organics and Kroeker Farms use conventional potato seed for their operations due to lack of access to organic seed. There have been some growers who have tried to produce organic potato seed over the years.

In 2010, Hoogland Farms in Millet, Alta. had the opportunity to buy some land which had been used for organic production. Through their seed potato salesman at the Edmonton Potato Growers, they were told there was interest in organic seed potatoes from farmers market potato growers.

Before purchasing the land, they also talked with a commercial organic farm, Fraserland Organics in Delta, B.C., who they already sold seed to asking if they’d be interested in organic potato seed. Fraserland was and were willing to pay the premium for organic potato seed.

“(Fraserland Organics) were decent sized customers. So, we thought, ‘Okay, maybe this is the way to try it.’ Because I mean, only for garden marketing it wasn’t worth it,” Jake Hoogland explains in a phone interview.

They started with a quarter section of organic land running a four-year rotation, growing 12 to 20 acres of organic potato seed. As a conventional seed potato grower, Hoogland had to learn the ropes of organic production, having to start summer fallowing and growing cover crops to reduce weed pressure. He also worked out a deal with a chicken farmer located an hour away to receive manure to fertilize his crops.

“Our customer in B.C. was fantastic — they supported us the whole way. And then on top of them we had a few market gardeners, but other than that no one else ever really bought organic seed from us. Main reason we were asking about 50 per cent over conventional seed — which we figured in doing our cost and putting summer follow in and you name it, all the inputs — we figured that that will be a very fair value for organic seed,” Hoogland says.

They were unable to find any other commercial organic growers besides Fraserland Organics who would buy seed from them. Eight years later Hoogland decided to pull the plug on his organic seed potato venture going back to fully conventional potato seed production.

“I just think the regulations are not set up properly. I understand that if there’s no organic seed available that someone can buy conventional seeds. But if it’s available, who’s going to check that? The regulations are just not tight enough,” he explains.

Rempel finds the policy allowing for conventional seed to be used is good as it’s hard to find organic seed. He understands the struggles there would be to produce organic seed as Kroeker Farms has their own potato seed production farm located in Saskatchewan.

“I think it would be way more difficult to grow organic potatoes from organic seeds. You want to start off with very clean seed,” he adds. “We do look for organic seed, but with the system there can’t be any chemicals on that seed, the seed has to be totally chemical free.”

The Future of Canadian Organic Potato Production

In the grand scheme of things, organic potatoes are a small part of the organic industry in Canada making up only one per cent of total organic production. There are approximately 226 organic potato producers in Canada while there are nearly 6,000 certified organic farmers in total, according to COTA.

“I didn’t expect it would be so low because any kind of root vegetable is a huge opportunity for farmers in Canada, because they last so long. But it’s interesting to see that we don’t have that many that are focused on potatoes,” Tia Loftsgard, executive director of COTA, says in a phone interview.

Loftsgard does think there’s opportunity for expansion in the Canadian organic potato industry. COTA has been participating in a supply chain project with the Canadian Organic Growers where they examine organic product categories. One of the crops that they have investigated is carrots — another root vegetable which is able to be grown in Canada and stores well.

Through the project they’ve found retailers are sourcing year-round product from reliable external suppliers, except for those that have made a commitment to sourcing local. In the next phase of the project, they plan to interview retailers and find out what the barriers are to sourcing locally so that COTA can help remove these and allow for more local organic products to be sold.

“I think that there’s a lot of knowledge that was attained through the supply chain project that we were involved in. But I think we need to get the word out there that wow, there’s a real opportunity for potato production happening in Canada that we’re missing out on,” Loftsgard says.

Overall, the organic industry has been growing. Nate Powell, an organic farmer who owns Cold Springs Organics in Belgrade, Mont., has seen the organic industry expand substantially since he first entered it in the early 2000s.

“Organic consumer education and awareness is only getting better. And there’s a lot of interest, especially in years like this, when folks are facing erratic fertilizer prices, really, really odd weather conditions, where trying to figure out how do we build a more resilient farming system is top of mind,” Powell says in a phone interview.

For Martien, he would like to expand his organic potato production but there’s a lot to consider first. If he grows too fast, he could end up with more land than he can handle and be unable to check fields as much as needed or do the required field work in time. Farming on P.E.I. also means there’s a limited land base and even more limited land available that has been used for organic production.

“We’re not able to do land trading that a lot of farmers around here do where they’ll trade for corn or soybeans with neighbouring farmers. Unless you’re an organic farmer and you want to trade, like say an organic grain farmer, trading is not really an option,” he says.

However, he does believe overall there’s room for more organic potato growers in Canada. Martien was concerned recent food price inflation would drive consumers to buy cheaper food instead of organics, but that hasn’t happened, and he’s even seen increased demand in some cases. He isn’t the only grower seeing increased demand.

“We’ve had no problem selling our organic potatoes and onions. And every year we wish we could grow more because of the market share,” Rempel says.

Organic potato market demand is increasing and while it does take more work to grow spuds, both Rempel and Martien agree the industry has room to grow.

Header photo — A field of flowering organic potatoes at Hakkers Organics in Newtown Cross, P.E.I. Photo: Hakkers Organics

Related Articles

Peter VanderZaag is Bringing Canadian Bred Spuds to the World

The Regenerative Ag Debate for Growing Potatoes, is it Possible?