Entomologists not ready to throw in the towel against nasty pest — Colorado Potato Beetles.

The Colorado potato beetle continues to frustrate farmers and take its destructive roadshow across Canada. One reason for this is they are highly adaptive to control methods and simply hard to kill. And yet, despite the dour outlook, farmers still have many options available and there is reason for optimism.

Research from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) from coast to coast is underway to arm farmers with as much up-to-date information as possible to keep the nasty pest from decimating any more potato fields.

Led by co-principal investigators Chandra Moffat in the Okanagan, B.C., and Ian Scott in London, Ont., the project dubbed Development of Regional Management Strategies and Decision Making Tools for Control of Colorado Potato Beetle will inform farmers of where beetle hotspots are, what chemistries have been losing efficacy — critical for rotational chemistry options — and even what molecular markers are changing within the beetle’s genetic structure to give faster clues to control them and swap chemicals.

The five-year research project ends in 2023, but with three years of data to pull from, there’s already relevant takeaways for potato farmers, including how the neonicotinoid (neonics) class — arguably the most popular — of insecticides has continued to lose ground over the years.

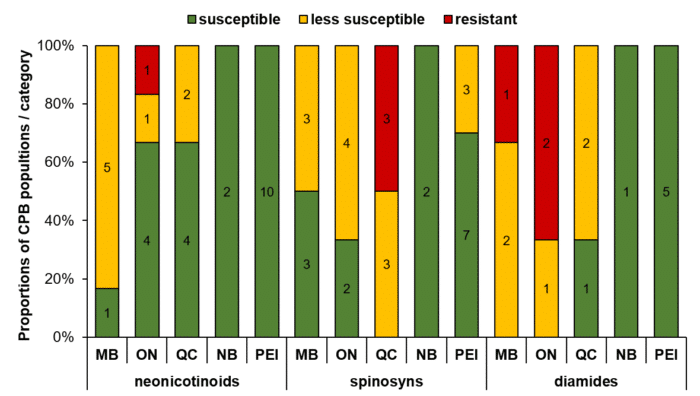

“With the neonicotinoids, that’s where we are seeing the greatest indications of reduced susceptibility and resistance in some cases,” says Scott. “It’s not so much of a surprise due to their long use in Canada, but we are quite interested in the fact that many growers are seeing similar reduced susceptibility with the spinosyns, which includes the only product registered for organic production. Products in this class are often used as a mid-season foliar spray, just in case the early season seed treatment loses its effectiveness partway through.”

This development is of concern because the use of the spinosyns, as well as diamides, as insurance sprays, may contribute to reduced efficacy over time. However, farmers are put into seemingly impossible positions of protecting their crop versus losing it.

Luckily, farmers do have options. There are multiple chemistries commercially available and a concerted rotational effort to not overuse one over the other will help extend the chemistries’ lives. As well, crop rotation is another cultural control that helps reduce or slow the beetles’ overall population growth. It is always recommended to have at least two non-potato years after growing the spuds, if not more.

“Building soil health has such a major influence on crop productivity,” explains Moffat. “Where we see soil health, we see less pressure.”

The regions that are being investigated — Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and Prince Edward Island — are showing different levels of beetle pressure in general in addition to varying levels of resistance to certain insecticides, as well.

Generally speaking, farmers in Eastern Canada have “a bit more time,” with getting good results from neonics and diamides compared to Western Canada, according to Moffat, but not much.

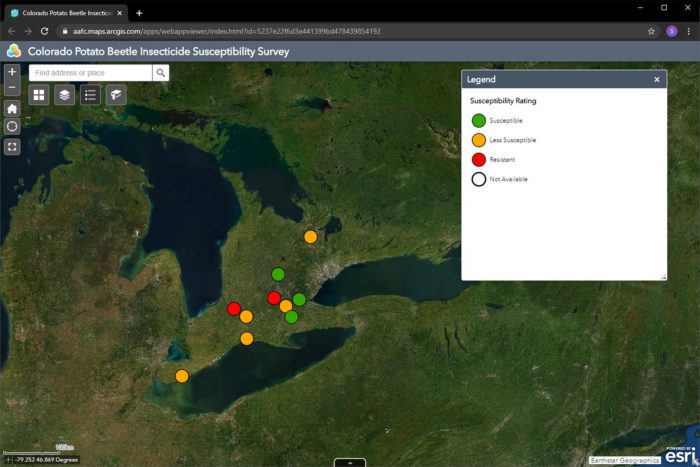

In Quebec, for instance, they are now in an intermediate category of “reduced susceptibility,” which means while some chemistries still work, they don’t work like they used to. The team operates on a simple traffic light system of control where green means 70-plus per cent control, yellow is 30-69 and red is 0-29.

Currently, Manitoba and Ontario are largely in the red when it comes to neonics and diamides, which may be a harbinger for Quebec.

The problem is as much the lack of chemical rotation as it is how fast the beetle adapts. Within two seasons, research has shown that beetles are able to adapt to new environments and products.

“Pressure from the Colorado Potato Beetle is not a problem that will go away,” says Moffat. “We have to make the best use of the tools we have at hand, and we want to help growers do just that.”

Real Time Monitoring of Colorado Potato Beetles and Molecular Testing

Like all things in this day and age, everyone demands instant gratification. The same is true of potato growers and boy would they benefit from it. Moffat and Scott’s research is now extending itself out into real-time data, which farmers can see through desktop computer or on a smartphone app, currently in development. The interactive map of Canada shows specific growing zones along with the traffic light system of what beetle pressure has been like in that area as well as what chemistries have been recently used.

“That will inform them if the beetles are resistant to neonics in a number of local populations,” says Scott.

To date, more than 30 farmers who face consistent beetle pressure have partnered with the researchers to be representatives for a specific region.

The ultimate goal is to have the tool be a real-time aid for farmers as they make agronomic decisions both pre-planting as well as in-season.

Photo: Chandra Moffat

Beyond monitoring, work is also being done to test the molecular structures of beetles, to see what genes inside them may be evolving season to season as it adapts and develops resistance to certain insecticides. By understanding which beetle populations are changing, and at what rate, researchers will have another detection tool, this time micro-RNA, which can be used as an early resistance marker.

“Over the last three years, we found that a number of genes could be potentially used as indicators of the resistance,” explains Scott. “We are hoping to repeat collections where they saw resistance in the past to confirm that there is a consistent increase in these genetic signatures.”

If the genetics show continual change from the same growing region, it’s a good indication resistance is building, and susceptibility is failing. That’s very important to know. To detect this, it used to be a yearly process. Researchers would test the beetles in a lab, process results and eventually get results to growers post-harvest. For many, that was simply too late as insurmountable losses already told farmers what they needed to know.

The hope is now this molecular testing, co-led by molecular biologists Cam Donly (AAFC) and Pier Morin (Université de Moncton), could be a new tool available to farmers mid-season so they can adjust their product of control, if resistance is present.

“So many other studies look at populations once they’re resistant,” says Moffat. “We want to see fingerprints of resistance developing so there could be a tool to see it change in real time.” For their dream to come to fruition for farmers, it means a few more years of work in the lab.

A Field View of the Colorado Potato Beetle Problem

Tracy Shinners-Carnelley works with many Manitoba potato growers through in her role at Peak of the Market grower co-operative and says neonics’ downward efficacy spiral is of concern, but Moffat and Scott’s research is reason for optimism.

Her farmer members have found positive results of backing off certain chemistries where reduced susceptibility resistance was showing, only to later re-use it a few years later and found it has a stronger effect.

“As an industry using these tools, we need to know how to best use them to keep them around as long as possible,” she says of chemistry breaks. “Maybe that will be a strategy that will ultimately allow us to keep multiple classes of chemistries for the longer-term rather than using one class to the point where beetles are quickly resistant.”

Colorado Potato Beetle Research Project Break Down

The scientific team for this research project is AAFC research scientists Chandra Moffat, Ian Scott, Jess Vickruck and Cam Donly, AAFC GIS and mapping specialist Sheldon Hann and professor Pier Morin at Université de Moncton. There are several project partners from potato growing regions across Canada.

The project began April 1, 2018, and runs to March 31, 2023, and is funded annually by the Canadian Agri-Science Cluster for Horticulture 3, in co-operation with AAFC’s AgriScience Program, a Canadian Agricultural Partnership initiative, the Canadian Horticultural Council and industry contributors.

Cover Photo: Adult Colorado potato beetles feeding on a potato plant. Photo: Tracy Shinners-Carnelley, Peak of the Market