Although the transmission and incidence of Potato virus Y in Canadian potato crops has declined dramatically over the past eight years, new threats to quality and yield are on the horizon in the form of necrosis-causing novel strains. How can Canadian growers manage PVY on their farms today, and how do they fight these latest strains?

For this edition of Roundtable, Spud Smart sought input from industry experts Mathuresh Singh, director of Agricultural Certification Services, and Anne McRae, a technical service specialist for insecticides and horticulture products at BASF Canada, on how to manage PVY, what tools are available for growers, the challenges researchers and growers are up against, and new tactics and control products researchers are developing.

Plant Clean Seed

Potato virus Y originates from different sources of inoculum to infect potato crops. Sources of PVY inoculum include potato seed, neighbouring fields, and in-field volunteer plants, weeds, and cull piles. Once PVY is introduced into a field, it multiplies and eventually affects the harvested crop by lowering yield, reducing potato quality due to necrosis, and seed certification failure, says Singh.

Based on studies carried out in New Brunswick on PVY management, certified seed use with low or zero PVY percentages has had a dramatic effect on planted PVY levels over the past eight years. In 2011, only 35 per cent of acres planted had PVY levels between zero and one per cent compared with 92 per cent of acres planted in 2017.

The decline in PVY levels of planted acres can be attributed to the post-harvest testing program and growers’ use of extensive management tools, says Singh. “Since growers have been planting clean seed, our post-harvest testing has been offering us very good results,” he says.

The decrease of planted PVY levels is a major factor in the decline of potatoes harvested with PVY. Between 500 – 700 seed potato lots have been tested yearly since 2009 to determine the average percentage of PVY in harvested seed potatoes. According to Singh, in 2009, the average percentage of harvested PVY was close to 12 per cent, however in 2016 that figure declined dramatically to 0.43 per cent.

“One of the best management tools is to plant clean seed with a low PVY percentage. This is the most cost-effective way to reduce PVY at harvest,” says Singh.

According to his study results, PVY levels are low — less than one per cent — on farms where growers only produce high-quality seed. Growers producing more than 30 per cent seed potatoes but less than 70 per cent table or processing potatoes have higher PVY levels on their farms. Growers producing more than 70 per cent table or processing potatoes and less than 30 per cent for seed have almost twice the PVY levels on their farms compared with those who only grow seed.

“This indicates even though the growers are planting good, clean seed, the PVY is moving within their farms from different fields. Also, the PVY could be coming from infected plants growing in cull piles or from field volunteers. This should be avoided by rotating fields with non-potato crops, which also helps reduce PVY,” he says.

Singh also suggests to clean cull piles and get rid of volunteers.

Mineral Oil and Insecticide Applications

PVY inoculum can originate from seed and from different fields — but how does it move from one field to another, and how is it transmitted from plant to plant? Aphids are one of the main vectors for transmitting PVY, and there are almost 60 different aphid species that can carry PVY.

Aphids transmit PVY between fields and from plant to plant. Extensive work has been carried out in New Brunswick, says Singh, on managing aphid PVY transmission between potato fields and plants with a horticultural mineral oil and insecticide tank mix, which is sprayed to reduce aphid PVY transmission.

“Insecticide sprayed alone is not very effective for PVY management, however, if we combine mineral oil with insecticide, it’s very effective,” says Singh.

Studies carried out in 2010 and 2011 indicate aphids can carry PVY early in the season and can infect a potato crop before the majority of the plants are emerged. Growers started their spraying programs after 50 per cent plant emergence with mineral oil or a combination of oil and insecticide.

Six different fields were sprayed with mineral oil and insecticide at two different times — three fields were sprayed on June 15 and three on June 29. The spread of PVY in fields sprayed on June 15 was quite low, says Singh, and those fields contained almost half the PVY levels as fields sprayed on June 29, which also showed a much greater percentage of PVY spread.

Based on the data generated from this study, Singh says he recommends spraying potato crops when they’re at 20 to 30 per cent emergence or earlier. “If we spray the fields earlier, we can manage PVY in potato crops better by protecting the majority of plants,” he says.

More research was carried out in growers’ fields between 2010 and 2014 to determine optimum spraying frequency. The study results indicate moderate spraying frequency (six to eight times in-season) of a mineral oil and insecticide tank mix on potato fields produced higher PVY spread percentages than potato fields sprayed at an intensive spraying frequency (12 to 13 times in-season). The mineral oil used as a tank mix ranged from 1.5 litres to almost three litres per acre, with an average around two litres.

Fields planted with processing potatoes, which were not sprayed, had the highest PVY spread percentages.

Those trials were replicated for three years using two different oil regimes, says Singh. The fields that were not sprayed (and used as a control) had a PVY spread around 10 per cent. Fields sprayed with insecticide weren’t far behind that value, indicating insecticide alone doesn’t really help manage PVY, says Singh.

However, in those fields where insecticide and mineral oil were combined and sprayed, “there was a huge difference between the control and the insecticide or mineral oil tank mix,” he says.

In addition, application of mineral oil alone reduces aphid PVY transmission greatly when compared with the control; however, insecticide combined with mineral oil produced the lowest PVY spread percentages.

Where insecticide and mineral oil were combined, 1.5 litres was sprayed throughout the season in one trial, and three litres was sprayed for five applications and was then reduced to 1.5 litres in another.

Insecticides found to be most effective with the mineral oil tank mix are lambda-cyhalothrin (Silencer) and flonicamid (Beleaf) as well as some other pyrethroids, says Singh.

“The lambda-cyhalothrin is a cost-effective insecticide, and it is very effective for aphid management when combined with mineral oil,” he says.

Challenges Ahead

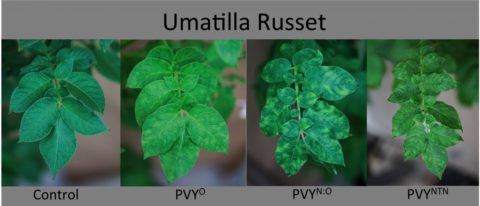

PVY isn’t one virus but several virus strains. There are currently three known groups of strains: the common strain, PVYO, and the novel necrotic strains PVYN:0/N:Wi and PVYNTN. The necrotic strains can cause tuber necrosis, affecting a potato crop’s quality and yield. Recently, PVY populations have been shifting from the common strain, PVYO, to the necrotic strains.

Furthermore, the symptoms these novel strains cause vary with the strain type and the potato variety it has infected. For example, when infected with the three different strains, Ranger Russet leaves can exhibit three different symptom sets.

The novel strains are also more cryptic — they’re hard to see and rogue from a potato field. Additionally, these novel strains can spread quicker than the common strain, PVYO.

effects different strains have on potato yields and quality is important information for decision-makers. Photo courtesy of Mathuresh Singh.

Climate change, the shifting availability and costs of effective insecticides, and the unknown susceptibilities of new potato varieties is making managing these novel strains more complicated, says Singh.

“The new potato varieties released each year respond differently to each strain, and the cost of insecticides can fluctuate. In addition, growing season temperatures are on the rise and winters are very mild, so aphids are surviving. These factors are complicating PVY management plans,” he says.

A single application of mineral oil is roughly $15 per acre, and for insecticides from $5 to $22 per acre. Although mineral oil and insecticide applications could be added to growers’ weekly spray programs for late blight management, depending on how many applications are required, growers should expect to pay about $200 (moderate spray frequency) to $335 (intensive spray frequency) per acre for PVY management (mineral oil and insecticide).

New Tactics

Recently, Singh’s team finished a project to determine the major PVY strains’ symptoms produced in commercially-important varieties. The PVY strains were collected from all over Canada, and the symptoms produced in approximately 30 varieties were catalogued.

“Only four varieties showed symptoms in tubers, the rest did not — which is good news,” says Singh.

Cataloguing these symptoms will help growers recognize PVY infection in the field. In addition, measuring how different strains affect potato yield and quality is important information for decision-makers, he notes.

At this time, the researchers also explored mechanical PVY transmission in the field during cultivation. Results from this study indicate the PVY transmission rate between plants — in particular for necrotic strains — was three to four times the rate in rows where tractors were allowed to pass compared with rows where tractor access was restricted.

“We found where tractors were being used for spraying and for cultivation, mechanical transmission of PVY was taking place in the field,” says Singh. “That explains why, even if you plant low PVY seed, it can still be transmitted by tractors as mechanical transmission.”

Other ongoing research efforts include identification of other effective insecticides which are also low in cost and have low environmental impacts. Recently, Singh was involved with a project that developed some of the markers to be used to screen germplasm for breeding programs and the future development of new PVY resistant varieties.

However, at the moment, growers should be focusing on spray applications to reduce aphid transmission to manage PVY in their fields.

“I emphasize most of the work we have done in New Brunswick and also in Manitoba has been on the management of PVY using mineral oil and insecticides. We’ve found it’s very effective in both Eastern and Western Canada,” he says.

New Insecticide Tool

BASF has created a new insecticide called Sefina which can be used for PVY management. The insecticide has a novel active ingredient (afidopyropen), which BASF has named Inscalis, for the control of piercing and sucking pests, such as aphids. The product is currently being reviewed for registration in Canada, and is on track for the 2019 season for use on potatoes, as well as soybeans.

“Two of Sefina’s key characteristics are the quick onset of feeding cessation and its extended duration of control,” says McRae.

In addition to vectoring pathogenic viruses, aphids, when present in high numbers, can cause wilting damage by sucking nutrients from foliage and stem tissue.

“By stopping aphid feeding quickly with Sefina, we can reduce the risk of spreading harmful viruses like PVY and limit feeding damage for up to 21 days,” says McRae.

One issue with insecticides is the length of time they take to work, allowing aphids more time to feed and spread viruses.

“I heard once, aphids can’t walk and chew gum at the same time. A moving aphid is not a feeding aphid, but a stationary aphid is a feeding aphid. Sefina takes effect around the 11-minute mark. When spraying your potatoes, Sefina will be working before you’ve even left the field. If an aphid cannot pierce the leaf it cannot spread the virus,” says McRae.

Sefina controls both green peach and potato aphids, which both carry PVY. Because aphids are affected when they are sprayed with the insecticide as well as when they ingest it from leaf tissue, the product works for up to 21 days.

The product is translaminar, so it moves from the top of the leaf to the bottom, however, it is not systemic, so it doesn’t move through the plant. It’s important the whole plant is covered when applying the insecticide, notes McRae.

The first to be classified in subgroup 9D, this pyropene is a neuromuscular disruptor in a new chemical class with a unique mode of action. Thus adding another tool for growers to manage insecticide resistance. “There is no cross-resistance to any other insecticides,” says McRae.

As a neuromuscular disruptor, the insecticide is fast-acting, working within the first 24 hours.

Sefina is a chordotonal organ TRP-V channel modulator, says McRae. Basically, chordotonal organs are responsible for sensors in the antenna, legs, mouth, wings and thorax. They provide insects with their senses of hearing, orientation, balance and coordinated movement.

When an aphid is exposed to the insecticide, it locks the TRP-V channels open and chordontonal organ feedback is blocked, she says. Sensory neurons send continuous and misleading signals, so the insect’s brain can’t detect sound, gravity or body movement. The aphid will make odd sporadic movements, so it appears drunk or as if it’s dancing around. It is then unable to pierce the leaf to feed.

The insecticide also has a low impact on predatory and parasitic insects, such as lady beetles. “Which makes it an excellent resource for integrated pest management,” says McRae.

“By protecting our predatory insects, they are able to move to other fields, or come back again to help us manage aphid populations later in the season,” she says. “Sefina is an excellent resource for growers’ integrated pest management programs.”