Over the last 30 years, potato production in China and India has increased at a dramatic rate, largely due to area expansion. In 2009, these two countries produced one-third of the world’s potatoes. In addition to area expansion, production growth is now being driven by other means. Consumer demand and consumption trends are also influencing how the industry is growing and at what pace.

China: Aggressive National Policy

If the vice-governor of Ningxia province in China is spending his downtime dreaming up recipes for his potato cookbook, you can bet this country is focused on potatoes. Qu Dongyu, with colleague Xie Kaiyun, recently published “How the Chinese Eat Potatoes,” which contains hundreds of recipes as well as historical, nutritional, production, and distribution information on the potato.

An influential voice in promoting potatoes in China, Qu is one of many former students of Canadian potato farmer and researcher, Peter VanderZaag.

“If a vice-governor of a province puts his mind to publishing a book about how to eat potatoes in China, they’re serious about potatoes,” says VanderZaag, who is also the board chair of the International Potato Center (CIP) of the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research in Lima, Peru.

VanderZaag has been travelling to China for 26 years to guide policy and provide direction on potato production at a national level, as well as train and educate scientists, and work on the practical aspects of potato farming with Chinese farmers. He has witnessed first-hand the dramatic growth in production, which increased 279 per cent from 19,328,100 tonnes in 1969 to 73,281,890 tonnes in 2009 (FAOSTAT*). This growth is likely to continue considering the focus of the latest five-year plan released in March by the Chinese government.

The 12th five-year plan is ambitious: the main focus is to reduce the number of people now living in poverty (roughly 100 million) by half. And one of the champions of this great challenge is very humble indeed—the potato.

VanderZaag, who met with China’s agriculture minister last April, says the government is aggressively pursuing food security and the elimination of poverty by growing potatoes. “In China, the government is putting its money where its mouth is. The five-year plan is to almost double potato production. They are putting hundreds of millions of dollars into this venture to make it happen,” he says. “The government’s real focus is to help the poor areas improve their standard of living and economic status. They really believe potatoes are one of the key contributors to this.” China is already the number one producer of potatoes in the world, growing 22 per cent of global output (FAOSTAT). The government’s focus on more growth could mean production of about 120 million tonnes by 2015, says VanderZaag.

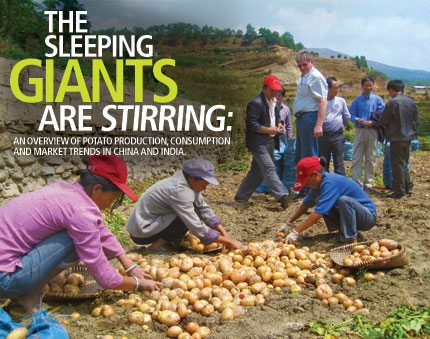

According to the five-year plan, more potatoes will be grown by farmers in the mountainous regions of northwest and southwest China, says VanderZaag. In those regions, farming is intensive on small-scale farms with as many as 100 growers in one valley, each growing less than two acres.

The choice of growing more potatoes in these areas is a calculated one: “The government of China knows potatoes are the most efficient converter of sunlight into energy, they know the value of its protein, and they recognize it as the most effective crop to deal with the poverty pockets of China. What else can they grow there as well as potatoes—nothing,” says VanderZaag.

These regions are home to some of the nation’s poorest people, therefore this high-value cash crop will put money directly into the pockets of the people who need it most, also addressing the existing disparity between people living in the more prosperous coastal regions and those living in the poverty pockets of the mountainous areas. “What [the government] is doing now is they’re rebuilding villages in the mountain areas with good homes. They want farmers to grow better crops of potatoes to sell, and to get good money for them,” says VanderZaag. Right now, farmers in China are fetching an excellent price for their potatoes. “The price farmers were getting in the field in May was approximately 33 cents per kilogram. Any [Canadian] farmer would be envious of that price,” he says.

The main goal is production for table potatoes, for food, but the potential for growing for other sectors is there. VanderZaag notes the Chinese government is also looking aggressively at the processing industry.

Overcoming Constraints

Since economic reforms began in 1978, China has experienced increases in production quantity and area harvested of 156 per cent and 127 per cent, respectively, yet yield has only increased by 13 per cent (FAOSTAT). VanderZaag notes the average yield in China is 15 tons per hectare, which is relatively low when compared to yields in developed countries.

In the last few years, China has made some headway in overcoming agronomic and environmental constraints that contribute to the yield gap. For example, according to VanderZaag, farmers in Yunnan, located in southwest China, have recently harvested 85 tons/hectare of a new variety called Cooperation-88, a CIP-developed variety introduced by him. This variety, like others being tested in China, is proving to be better suited to the country’s environmental stress conditions than some traditional varieties. “The characteristics of the variety, in combination with good agronomic management, good seed, optimal irrigation and sunlight, have yielded some excellent results,” says VanderZaag.

C-88 is also showing amazing resistance to late blight and viruses, he says. Late blight is the most serious constraint to production in China. Right now, most farmers in the mountainous regions use backpack sprayers, but what they really want is resistant varieties, says VanderZaag.

Seed quality, yet another serious agronomic constraint, is also being addressed by China’s national policy. Last year, the government expanded its subsidy program to include seed potatoes. China is now developing a seed system of three generations of seed production. VanderZaag says the government is aggressive about getting good quality seed into farmers’ fields, and already the country is benefitting from this action. “There has been a quantum leap of improvement in productivity from just that one factor,” he says.

Inserting potatoes into the cropping sequence of shorter duration wheat and rice varieties in southern China is also allowing farmers to expand potato production area. “Potatoes are so profitable, they can’t afford not to grow them in the sequence,” says VanderZaag.

Another initiative by the government of China is its continued commitment to potato research and development through its investment in a new research facility. On February 5, 2010, CIP signed an agreement with the government of China to proceed with the building of the CIP-China Center for Asia and the Pacific, to be based near Beijing. VanderZaag says he visualizes a staff of 60 international scientists in what he calls an incubator for research. Here, scientists from around the world will work with Chinese and Asian scientists, conducting mutually beneficial research. “The cross pollination or incubator idea is people sharing information together making the world smaller—a better place,” he says.

Increasing Consumption

Another major factor influencing potato production in China is consumption and consumer demand. Over the last 30 years, the potato has become a popular choice, showing up more often on the plate in the home and on menus in traditional and quick-service restaurants.

According to Qingbin Wang and Wei Zhang in a recently published paper in the American Journal of Potato Research entitled “An Economic Analysis of Potato Demand in China,” consumption has increased from around 10 kilograms per capita per year in 1986 to 35 kg/capita/year in 2003, and consumer demand is now a force to be reckoned with since China’s economic reform: “As China moves towards a market economic system, its potato production, processing, and trade are increasingly determined by consumer preference and demand.”

The authors state the number of consumers will likely continue to increase for a number of reasons, such as improved availability of potatoes in both production and non-production regions; consumption of potatoes by urban consumers will increase as incomes increase (this trend will be followed by rural consumers); the potato is considered an inexpensive and desirable vegetable to eat; potato products are increasing in popularity among young urban consumers; and China’s exports to neighbouring countries are expected to increase as a result of comparatively lower labour and transportation costs.

Wang and Zhang also note an increase in the number of consumers and amount of potatoes those consumers eat will influence production decisions made by farmers: “The production decisions of Chinese farmers are increasingly determined by the relative prices and profitability of alternative crops. As the demand for potatoes is likely to increase for meeting domestic and export demand, Chinese farmers are expected to allocate more of their resources to potato production.”

Frozen potato imports have also risen dramatically over the last 20 years. According to Wang and Zhang frozen potato imports (mostly frozen french fries) jumped from 661 tons in 1992 to 58,806 tons in 2006 due to increasing demand for Western-style food and QSRs. The authors note the number of McDonald’s restaurants in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan increased from 59 to 1,589 between 1987 and 2008.

According to the study, imports are likely to increase in the short term as demand increases. But in the long run, China may not become a large importer of frozen potato products because domestic production should also increase (already domestic and joint ventures involving foreign investment for potato production and processing are underway). Efforts are ongoing to produce potatoes in China that meet quality standards for McDonald’s and other QSRs. “In China, they are growing for the processing industry themselves. They are doing it and making it work, but it’s not always the best variety for their environmental stress conditions,” says VanderZaag.

Wang and Zhang conclude China may become an important player in the global arena, but not in the near future: “In the short run, China is likely to continue to increase its potato export and frozen potato import, but the impact on the world prices may not be significant due to China’s limited shares in the global trade quantities.” But in the long run, the report states, China could become a large exporter of fresh potatoes, largely to its neighbours, and a net exporter of frozen french fries and other potato products, increasing competition for North American potato exporters in the global market.

VanderZaag agrees that in the future competition among exporters may be stiff, but China’s ultimate aim is self-sufficiency. “They want to produce 50 million more tonnes—and that goal is for their own consumption.”

So will increased potato production in the next five years disrupt the profitable balance of supply and demand China is experiencing right now? VanderZaag thinks not. “If you look at the trend over the last 20 years, China has more than doubled—almost tripled—its production, and prices are as good as ever.” Usually excess supply means lousy prices, but this hasn’t occurred in China, he says. Consumption patterns may shift a little in the south, but this densely populated region can easily consume those potatoes. In the north, there is the potential for an excess because the area is sparsely populated, says VanderZaag. But shifts and adjustments in supply and demand may compensate for increased production; for example, most of the production growth may happen in southern China, with the north producing more seed for the areas in the south. Also, the french fry and chip sectors will keep growing, and, by and large, much of the extra production will be used for table potatoes, says VanderZaag.

China’s share in the global potato trade may be small right now, but the influence of national policy, the focus on overcoming environmental and agronomic constraints to increase yields, as well as the direction of current consumption trends should greatly increase production in the next five years. In the future, China may emerge as an important global player, but for now, this sleeping giant only stirs, not making enough movement to shake global markets.

India: Astonishing Growth

Over the last 40 years, India has experienced tremendous growth in potato production, increasing 628 per cent, from 4,725,500 tonnes in 1969 to 34,391,000 tonnes in 2009 (FAOSTAT). In 2008 and 2009, India slipped ahead of Russia to become the second-largest potato producer in the world (FAOSTAT). India has experienced an increase of 249 per cent in area harvested over the last four decades, as well as an increase in yield of 109 per cent.

India’s government has a long-established and serious commitment to potato research and development—the Central Potato Research Institute, established in 1949, has 27 research stations across India, employing the second-largest number of potato researchers (after China) in the world. As Hubert Zandstra, director general emeritus of CIP and board member of the World Potato Congress, notes, “India has had a long-standing capability of developing local varieties.” The institute has developed many varieties suited to India’s growing conditions, such as heat- and drought-tolerant varieties, greatly contributing to the country’s potato productivity.

India is also committed to addressing poverty issues through potatoes. “The director general of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research is very strong on promoting potatoes as one of the ways to reduce poverty in the northern parts of India,” says VanderZaag.

But national policy does not influence production to the degree that it does in China. Although strongly encouraging potato production, the Indian government is not as radical as China in its tactics to increase production, mainly because of money, says VanderZaag. “China is more aggressive and more focused, pouring money in to make it happen. India doesn’t have the luxury of extra money.”

Drivers of Growth

One of the most important influences on production growth over the last 15 years has been the increase of cold storage facilities, says Zandstra. According to data from CPRI, India now has 5,386 cold stores with 3,023 dedicated to potatoes.

While India’s ability to produce and distribute good quality seed has improved in general over the years, cold storage has also influenced the production and availability of seed. Seed is now being moved from the mountains to the lowlands. “They can grow seed up in the Terai and mountain regions and make that available for the south,” says Zandstra.

Investment in supermarkets and cold chain infrastructure is also driving production growth, according to Charles Crissman, CIP’s former deputy director general of research, in a presentation he made to the Potato Association of America in 2008. He also noted that the supply and quality requirements of the potato industry in India stimulates vertical arrangements, also increasing production growth.

Area expansion through crop intensification will also be an important factor for production growth in the future. “In the region of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, there has been a tremendous expansion with the introduction of potatoes into the multiple cropping regimes created by short-duration wheat and rice varieties. This is a fairly recent development, and there’s still a lot of expansion possible,” says Zandstra.

But one of the most important drivers of production growth is the money farmers can make by selling potatoes as a cash crop. “Farmers, and the income they can generate from including potatoes into their production systems, are driving this expansion,” says Zandstra.

Although production has greatly increased through acreage expansion, yields remain relatively low at around 17 tons per hectare, according to Zandstra. But in the future, the development of disease- and virus-resistant varieties could help narrow the yield gap. “At the research level and in the research institutes there is a desire and a lot of work conducted on trying to get more varietal resistance to lessen disease, but it’s got a way to go,” says Zandstra. He also notes that India is a good candidate for the use of transgenic or cisgenic (transfer of genes from the same species or close relative) crops to reduce yield losses from insects and disease, particularly, late blight.

Rising Consumer Demand

The demand for potatoes and potato products is also on the rise, contributing to production growth. Consumption of potatoes has increased from around 9 kg/capita/year in 1986 to 18 kg/capita/year in 2007 (FAOSTAT).

Keith Fuglie, branch chief for the Economic Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture, says the potato is a preferred food in terms of demand, and as incomes rise, Indian consumers are buying more potatoes and potato products. Although most of the potato production in India is for the fresh market, one emerging trend is an increase in consumption of processed potato products.

India’s emerging processing industry is growing rapidly, according to Bir Pal Singh, director of CPRI, in a guest column of the December 22, 2010 issue of FoodProcessing360. According to Singh, the new millennium heralded large strides in the Indian potato industry as several processors in the organized sector, as well as the unorganized, expanded manufacturing capacities or established new plants—the major players included Frito-Lay, McCain Foods Ltd., Haldirams, Potato King, and Balaji Wafers Pvt Ltd.

Consumption of potatoes by the organized sector in 2009–2010 reached 970,000 tonnes, slightly less than three per cent of the total potato output, said Singh, with potato chips leading the way: “Out of the total potato processing in India nearly 89 per cent was consumed by potato chips followed by 9 per cent by potato flakes and two per cent by the french fries industry.” But the highest rate of growth now belongs to french fries at 20 per cent, followed by potato chips at 17 per cent and potato powder/flakes at 15 per cent. Singh forecasts that 4.25 per cent of the total potato output in 2013–2014 will be consumed by the organized sector of the processing industry (around 1.54 million tonnes).

And, in general, the snack food market in India is taking off. According to Crissman, the snack food market is worth about $3.5 billion per year and is growing rapidly. In his presentation, he stated the potato constitutes 80 per cent of the organized half of the snack market, driving potato production growth in India.

Despite rising urban incomes, a Western-style fast-food

industry has not developed as rapidly in India as it has in China, but that is changing, says Fuglie. “You don’t yet have McDonald’s chains everywhere. This is partly due to people’s dietary habits and government policies toward multinational participation in the food market and food procurement. But this is changing—rising disposable income, urbanization, and increased participation of women in the work force are increasing demand for convenience foods. And fast-food restaurant chains have been adept at responding to local tastes and food preferences in their menu offerings.”

Imports of frozen potatoes were only 4,854 tonnes in 2008 (compared to 95,617 tonnes in China), but this still represents a dramatic increase of 1,252 per cent from 1998 when 359 tonnes were imported (FAOSTAT).

As the middle class increases at its current rapid pace, demand for french fries and chips will continue to increase, says Zandstra. And the expansion of cold storage for seed and higher quality processing potatoes should help sustain the industry; thus, production growth in India will continue for the foreseeable future, he says.

In India, the popularity of the potato and increasing consumer demand could prove to be a mighty combination for increasing production. “There is no worry about lack of demand as the high status of the potato and its increased use as fast food and in curries will assure increasing demand and good prices,” says Zandstra.

But, increases in production and demand should not rock global potato markets. “Although we’re seeing production growth, it’s not going to affect world trade in the near future,” says Fuglie.

So for now, this giant of the potato-producing world sleeps on, happily dreaming of a good harvest.

Kari Belanger

*FAOSTAT is the Statistics Division of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Data is available at http://faostat.fao.org.

Editor’s note: CIP is dedicated to the expansion of potato production in Asia, Africa and South America for the reduction of poverty and to achieve food security on a sustainable basis.