Long before John A. Macdonald took office as this country’s first prime minister 150 years ago, there were potatoes growing in Canada. But before we go into the history of the potato, let’s go back to the very beginning.

Potatoes originated in the Andes in South America and were taken to Spain around the year 1500. However, another 200 years or so passed before potatoes were recognized as a useful food source and were grown across Western Europe.

Hielke De Jong notes that the potato became a major contributor to the European population explosion that started in 1750, which led to increased urbanization and supported the birth of England’s Industrial Revolution in the 1800s. De Jong is a retired Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada potato breeder, and has written many articles and book chapters on the history of the vegetable. In an award-winning article contributed to the American Journal of Potato Research last year, he states that the way the potato fed rapidly-growing populations “permitted a small number of European nations to assert dominion over much of the world between 1750 and 1950.

“Throughout its history, the potato has provided bread for the poor,” De Jong says. “Today it contributes to food security on a global scale. The potato has been depicted on postage stamps in many countries, and the many references to the potato in art, literature and folklore worldwide are evidence how it has become interwoven in the cultures of many societies.”

Early Canadian Cultivation

According to Donna Rowley, manager of the Canadian Potato Museum in O’Leary, P.E.I., potatoes arrived in Canada in the late 1700s. What happened in that province represents to some extent what happened in the rest of Canada.

“In the late 1840s and 1850s, the Island’s crop was devastated by the same blight that caused the Irish Famine,” Rowley says. “But ultimately, that was considered a small setback for the industry.”

The early settlers continued to clear dense forests and planted the crop between the stumps. “In 1918, the seed sector emerged as a new element to the industry,” Rowley notes. “With this introduction, the industry was stable for the next 80 years.”

Rowley points to another milestone – in 1920 – when a variety called “Irish Cobbler” was introduced, and by 1930, acreage of potatoes on the Island had doubled.

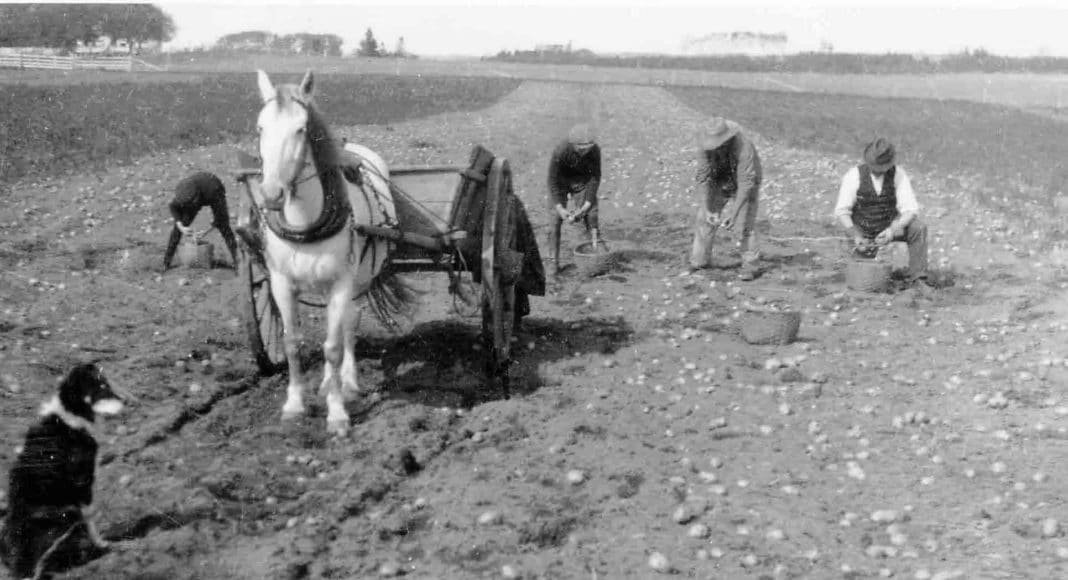

“Early farming equipment started with simple tools like horse-drawn plows and harrows,” Rowley says. “And a lot of the planting was done by tuber unit.” Farmers shook “Paris Green” on plants by hand to control potato beetles, and pulled scufflers, or horseshoes, behind a horse or two to remove weeds. Spraying for pests and harvest was also done by hand at first but eventually by using horse-drawn equipment. Beater diggers were common on the Island, says Rowley, and then elevator diggers and pickers. Tractors came on the scene and the size of the equipment grew. In 1940, Rowley says there were almost 11,000 potato farmers on P.E.I. growing 37,000 acres. In 1965, 6,500 farmers grew 44,000 acres and by 1990, only 650 farmers grew almost 75,000 acres.

Historic Trends

Besides better agronomic practices, and the use of technology, agrochemicals and irrigation, breeding has had a great impact on the Canadian potato industry. However, De Jong believes that any discussion of major developments here must take the big picture into account. “For example, when one discusses changes in varieties, one needs to emphasize that one of the major drivers over the last few decades for this has been changes in the collective North American lifestyle: a quicker pace of life and more desire for convenience foods which, in turn, increased demand for processed potatoes.”

When looking at all the varieties ever produced in Canada, many would say the most famous is Yukon Gold. This yellow-fleshed spud, created by Gary Johnston, is similar to some European varieties and hit a chord with European-born Canadians. After stints as a teacher and a Royal Canadian Air Force pilot during the Second World War, Johnston studied agriculture, and by 1953, was a research scientist with the Canada Department of Agriculture. He was later assigned to take over its potato breeding program at the University of Guelph, and was involved in the development of at least 15 varieties.

In 1998, two years before his death, Johnston wrote a remembrance for the University of Guelph Potato Research Program website, explaining that Yukon Gold was the result of a cross involving a variety called Norgleam from North Dakota. True seed was produced in 1966 and by 1980 the potato was ready for licensing. “I suggested the name Yukon for the Yukon River and gold rush country, and Charlie Bishop suggested we add the word gold, so it officially became Yukon Gold,” Johnston wrote. “To succeed I believed that [it] would require good publicity. Harrowsmith, a national magazine, published an article I wrote… and shortly after I was asked to do several interviews for TV and radio. The biggest boost came when two large Ontario growers printed Yukon Gold in large letters on their very attractive 10 lb. paper packages sold in many supermarkets.” This enabled customers, he wrote, to ask for them by name.

Challenges

One could consider low-carb diets to have been an enemy of the western world’s potato industry – and for much longer than you might have believed. In 1863, William Banting, a British undertaker and coffin maker, published a very popular weight loss booklet describing a diet that excluded potatoes, bread and other foods. Among other low-carb regimens in the late 1950s and early 1960s, there was the Eat Fat and Grow Slim diet, the Air Force diet and the Life Without Bread diet. The Atkins diet was introduced in 1972, but low-carb diets reached peak popularity during the late 1990s and early 2000s, when it is estimated that as much as 20 per cent of the U.S. population was on some type of low-carb diet.

A current challenge for the potato industry is public trust, a challenge with which all of agriculture is grappling. Today’s consumers have serious concerns about many aspects of livestock farming, and relating to potatoes and other crops, concerns include genetics, pesticides, water quality and much more. In late 2014, McDonald’s announced that it would not serve genetically modified potatoes, deciding that public trust in this type of potato was not high enough to risk their use. In 2016, the Canadian Centre for Food Integrity (a non-profit with members spanning the entire food industry, from John Deere Canada to Dow AgroSciences to Tim Hortons) released new survey results showing less than a third of Canadians believe this country’s food system is going in the right direction.

However, Canadian potato growers continue to build public trust. Besides using best practices on-farm, growers comply with the CanadaGAP food safety program, and through the United Potato Growers of Canada (UPGC), they’ve been involved with educational initiatives like Farm Credit Canada’s Ag More Than Ever program. Some processing growers also participate in the Potato Sustainability Initiative, a comprehensive program that promotes practices that result in reduced use of pesticides, energy, water, waste, greenhouse gases and more.

Moving Forward

The potato industry in Canada is vibrant. Many growers are quite young, often the offspring of immigrants who came to Alberta and other areas of Canada from places like the Netherlands 15 to 20 years ago, or the third or fourth generation in families who have farmed potatoes in Canada for much longer. Many of these younger farmers are Millennials (those born roughly between 1982 and 2004) and research by U.S.-based Millennium Research on younger midwest crop growers shows that Millennials differ in important ways compared with previous farming generations.

Although Millennials are more innovative and take more risks than their older counterparts, personal relationships are just as important to them as the latest technology. The research also found that these increasingly primary on-farm decision-makers are educated, business-savvy, gather information from diverse sources, and use the Internet selectively, preferring how-to videos and agricultural forums that help them solve their farming problems. They are loyal and want long-term relationships, and view farming as both a business and a lifestyle.

With Canada’s population continuing to grow and the low-carb fad seemingly just a memory – and with both Cavendish and McCain expanding processing capacity in the near future – the future seems bright for potatoes in Canada over the next 150-plus years.