Ohio State University looks into the messaging needed for consumers to buy imperfect produce.

Have you ever walked to the local grocery store’s produce section, only to see a bin full of “misfit produce”? Think about it: lemons with bruises, tomatoes with large buldges, or even carrots with two separate roots that look like a pair of legs.

There are plenty marketing campaigns aiming to uplift these imperfect vegetables — calling specifically that while blemishes might lower them from usual grocery standards, they are safe to eat and help minimize food waste in the fields.

Delivery services have also taken to misshapen vegetables, with direct-to-door services such as Misfit Markets and Imperfect Foods, delivering “ugly” produce straight to consumers doors.

When it comes down to it, though, what’s the perfect marketing information to sell to the consumer?

An Ohio State University researcher looked to see if explaining the value of these misshapen vegetables could improve sales of “ugly” produce.

“The food system is really designed around the consumer,” says Brian Roe, Van Buren professor in the department of agricultural, environmental and development economics at Ohio State University. “The success of the food system is whether or not food is actually consumed by a consumer. Everything else really has to be set up to ensure that occurs.”

When it comes down to it, misshapen produce is no different.

“Understanding the consumer is, in my opinion, fundamental for reducing waste throughout the system, and therefore making it more sustainable,” he says. “Ideally, it’s the last stop in the food system and not the landfill.”

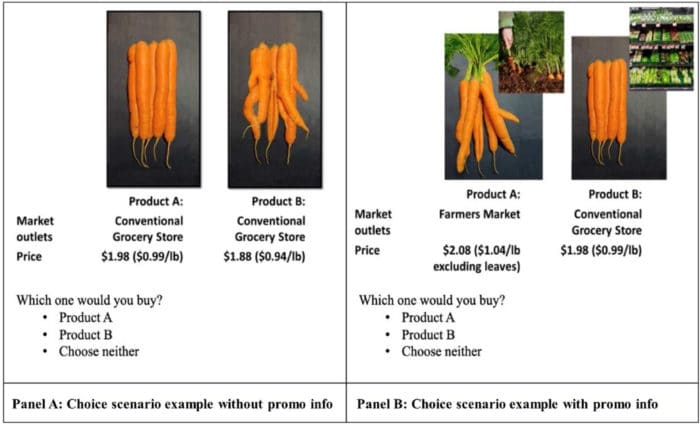

That’s where his study comes into play. The study measured consumer responses to hypothetical questions all around the idea of carrots. Participants were shown different images of carrots to see which they’d be more likely to choose and in what specific scenario.

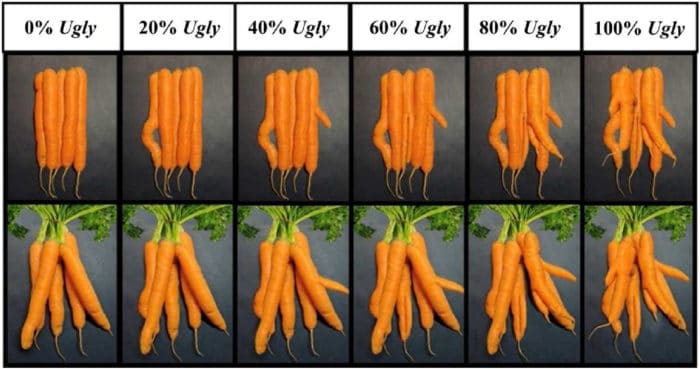

“We had two criteria. One: it had to be something that a lot of consumers were familiar with,” Roe says. “Then, it needed to work in our research, two-dimensional setting. In two dimensions, people can pick out whether carrots are ‘ugly’ pretty quickly, where other crops, like tomatoes, could be tricker.”

Using discounts from the marketplace where ugly produce was typically being sold, Roe and his team produced a scale to see what prices consumers would be willing to purchase imperfect vegetables at. Typically, these ranged somewhere between 10 to 40 per cent discounts in comparison to standard produce.

“It was calibrating what kind of prices and promotional elements change their willingness to pay for these products,” he says. “Uniformity is used as a signal as quality, but naturalness doesn’t always come in perfect uniformity.”

When it came down to the message, Roe says they worked to create a message that got across two separate ideas — a social idea and a private angle.

“You really need to emphasize two aspects of imperfect produce that make it potentially desirable to consumers,” he says. “A social angle, stating ‘If you buy these, it’s going to be less food wasted, and that’s good for society.’ Then a private angle, which is that these vegetables are just as nutritious and natural.”

Roe found that with these two messages were both included to consumers, they were willing to purchase misfit carrots at a discount than what they would pay in comparison to perfect, grocery store standard carrots.

Roe says that one potential direction to address this issue is to change the national standard. Currently, the national standard permits a particular fraction of items to be non-standard in shape or size — typically around 10 to 20 per cent.

“Another possibility here is just to increase that tolerance for misshapen items by a few percentage points,” he says. “Even if you can’t pull off a nationwide marketing campaign where you inform people about how wonderful it is, maybe you can increase the tolerance for misshapen carrots to enter into a bunch that still gets graded.

“We have some data showing that if you compared a bunch of carrots with one out of five imperfectly shaped and a bunch with two out of the five carrots were imperfectly shaped, there wasn’t much difference in terms of people’s willingness to pay the same amount for both.”

Roe says this suggests that there could be scope to increase the tolerance for imperfect produce before discounting the price.

“They just need graders to get used to allowing a little more wiggle room for wiggly carrots,” Roe says.