[deck]As profit margins shrink, it’s never been more important for growers to have a good handle on what’s happening in their fields. Data generated from yield maps provide insight on how to manage crops to improve profits, yields, or both. In this Spud Smart roundtable, Bill Menkveld and Shawn Paget ensure growers are getting the most out of their potato yield monitors.[/deck]

Bill Menkveld, vice-president of sales and marketing for Greentronics, has never met a grower who isn’t interested in yield maps. He says producers are often surprised by the results. “Growers are always amazed to see how much yield changes across a field. It’s not uncommon to see yields vary by a factor of 100 or 200 per cent,” he says.

Yield monitors provide information about crops and production practices and are designed to measure relative differences, and the degree of that variability, across a field. Yield maps illustrate areas of higher and lower productivity in fields. From this, growers can determine if zones of high productivity can do better and how to improve low-productivity areas or save costs on their inputs.

“A yield map is your farm’s report card on whether your management choices are helping to reduce variability, lower input costs, achieve optimum yields from areas with the highest yield potential or economize in areas of lower yield potential,” says Menkveld. “It’s all about learning how to manage your crop differently to improve your profit margin or yield, or both. And then to understand how your management is making changes over time.”

Although adoption of potato yield monitors continues to rise, some growers are still reluctant to map potato yields due to concerns about hardware installation and maintenance, and gathering and managing data.

Shawn Paget, owner of Riverview Farms in Simonds, N.B., says he was dubious about the returns potato yield monitoring would provide him. “I was a little hesitant about the cost and what I was going to get back out of it.” Now, six years on, he says he wouldn’t go without it. From the information generated by yield mapping, Paget says he’s working on increasing the productivity of his lower yielding areas.

“It’s getting better every year. I’ve taken some of the first fields we started working with and I’ve tweaked them and brought the productivity up,” he says. “When you have a yield monitor, you can see that. If you can’t measure it, you can’t count it,” says Paget.

Getting Started

Before purchasing or installing a potato yield monitoring system, the first step growers should take is to put a plan in place, says Menkveld. It’s a good idea for growers to consider why they want to monitor potato yields and what they will do with the data, before buying equipment.

“If you don’t have a plan in place — if you wait until you have all the data — it can be overwhelming,” he says.

After the yield monitor has been purchased, the installation and maintenance of the hardware is not difficult, Menkveld adds. Yield monitor hardware consists of load cells, which weigh the crop as it moves along the conveyor; speed sensors for monitoring conveyor speed; a GPS, which links data to location; and a data collection device, which provides the information to growers.

Although not a difficult process, Menkveld recommends growers take time to read the monitor’s operator manual for an understanding of the basic steps, and to ensure the system is set up properly.

Installation and Integration

Potato harvesters, like other vegetable harvesters, are very different from one another across brands and models, so Menkveld has designed a universal kit over the years, which allows the installation of potato yield monitors on a wide variety of machines.

If the monitoring system isn’t installed by a dealer, growers can install it themselves. It usually takes about seven hours for growers installing the hardware for the first time, says Menkveld. Although his company is always ready to help growers with installation queries, he says assistance is also available through authorized dealers or equipment manufacturers.

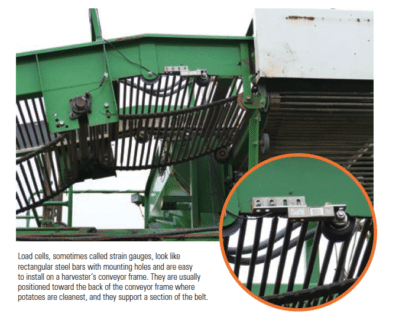

Load cells, sometimes called strain gauges, look like rectangular steel bars with mounting holes. They are easy to install on a harvester’s conveyor frame, are usually positioned toward the back where potatoes are cleanest, and they support a section of the belt. When potatoes pass over this section of the belt, the load cells convert the pressure from the weight into an electrical signal, which is combined with conveyor speed data generated by the shaft sensor, to measure weight over time. Tilt sensors can be added to the set-up to compensate for changing conveyor angles if needed.

Over the years, Menkveld’s operation has learned how to integrate his potato yield monitors with other companies’ displays. “There are some displays by Trimble and John Deere we can talk to directly. Growers see yield maps in real time on those displays, giving them instant feedback. Also, most of those displays have cell modems for convenient data upload to the cloud.”

If a grower is integrating a system, such as a Trimble or John Deere display, a technician from a dealership may be required to make that integration work, says Menkveld.

Once the installation is complete, Menkveld recommends using the test menus to analyze each component to ensure the monitor is working correctly. For example, growers should confirm the load cells are balanced and working correctly and the shaft speed sensor is operating properly.

Calibration of the system is important — the accuracy of the collected data depends on it. Menkveld recommends growers work through the calibration tools. Load cell output, shaft sensor reading and span calibration should be checked the first time the monitor is used and each new harvest season.

Zero tare calibrations must be carried out daily and when field conditions change for the system to work properly. These calibrations only take minutes, says Menkveld, but can’t be overlooked. “The yield monitor needs to know what the conveyor weighs when it’s running empty. You must have a proper baseline.”

When going from a dry field to a wet field, soil can build up on the conveyor. “Even though it doesn’t look like much, the soil can add a few pounds to the weight of the conveyor and if you don’t adjust for that with tare calibration, you’re constantly adding that weight to the yield data, which can start skewing the results. It doesn’t take long to do a tare calibration, only 30 seconds, but it’s something you have to do.”

Also, farmers should check their load weights. If a full truck at harvest should weigh around 400 hundredweight and the yield monitor is saying a very different number, something is off. Don’t carry on with harvesting, Menkveld says. “The adjustment is usually very simple.”

One concern growers have voiced about potato yield monitors is the accuracy of the data, particularly in heavy or wet soils. On sandy soils potatoes can be very clean when harvested. In heavy soils, wet conditions, or when a field has many rocks or clods, the potato stream is not as clean.

Menkveld says in his experience growers harvesting in heavy or wet soils, or fields with rocks or clods, still want yield maps, as they provide them with data they would not otherwise have. The point of a yield monitor is not only to measure weight pound for pound, but to measure relative differences and variabilities across a field, he says. “Even without post-season adjustments to account for debris, those results are useful.” He also points out harvesters today have greater separation capacity.

Paget agrees. “I am not going for the actual weights I’m putting into storage. I’m looking for variabilities in the field, and the yield monitor will tell me that,” he says. “If it’s off five per cent, it’s off five per cent in the high [productivity] areas and it’s off five per cent in the low [productivity] areas. It still gives you those ups and downs.”

Currently, Paget is collecting yield map data for his fields. He’s breaking his fields into five zones and soil testing in those zones, which is saving him time and money.

“We’re on a 2.5-acre grid sample now, so that’s a lot of soil sampling. I’m hoping by doing this, it will cut my soil sampling down by a quarter — so it’ll be a lot quicker. I’ll have the data back as soon as I finish the field. I’ll have the soil samples back within a week.”

By identifying major yield variability, growers can develop practically-sized management zones that can be managed individually, says Menkveld. He also agrees that a yield monitor is far more convenient than carrying out test digs by hand at different locations in the field. In fact, in general, yield monitoring has become far more important than it used to be due to larger field sizes, increased use of leased land, the use of bigger and more expensive machinery, increased input costs and land values, he says.

“Profit margins are shrinking and the only way you can do better is by reducing your costs and increasing your revenues. While there are many ways of doing that, really understanding and getting a good handle on what’s happening in the field is very important,” says Menkveld.

Precision Management

Yield maps when combined with others, such as soil, elevation, application, planting and population maps, as well as NDVI data and drone images, provide insights growers can use to drive increased productivity and revenue through precision management of crops.

Paget says Riverview Farms is moving in that direction, using variable rate fertilizer application to better manage fertility in his fields.

“We’re getting to the point where we can apply different rates of fertilizers for different areas of the field, as well as lime recommendations. We’re trying to bring those poor [yielding] areas back up.”

There’s no need to put fertilizer in a place where your yield potential is low, agrees Menkveld. Also, if a pivot doesn’t put water in the corners of a field, don’t put down a lot of fertilizer there because yield will still be low, he adds.

“You cannot begin to start that kind of management until you have the information, and you don’t have the information if you don’t have the technology. It all goes hand in hand,” says Menkveld.

Growers are also using variable rate irrigation on their farms — soil sensors tell an irrigation pivot how much water to apply in certain areas. More growers are putting down liquid fertilizer with irrigation water, which can also be mapped in-season and followed up with a yield map at harvest.

“You can see if what you did to improve management of irrigation sites actually resulted in better yields or margins,” says Menkveld.

Additionally, the newest planters offer variable rate adjustment of population density to spread the distance of the seed in the row. A map can be loaded to a planter so that the planter automatically changes its seeding rate as it moves across a field.

In addition to using variable rate fertilizer and lime applications, Paget says he’s just getting into variable rate seeding at his operation. He says he’ll try prescription seeding with his corn crops first and then move into potatoes. He has high hopes prescription farming will increase his yields.

Combining yield data gathered by the monitor on his combine with that collected from his potato harvester, Paget has multiple years of yield data from different crops, and sometimes they overlap, he says. “If you look at the averages, if it’s a high-producing area, it’s usually a high-producing area in every crop.”

There are many ways of collecting information from a crop, says Menkveld. However, it all comes together at harvest. With yield monitoring, farmers can examine the data and determine what was accomplished with their crop management efforts.

“Did the changes they made make a difference? Can they measure that difference? What can they do with the differences they’re seeing? Does something need to be done differently in the future? Have they maximized what they can do? Should they consider different varieties or plant spacing?” These are just a few of the questions Menkveld says growers should consider after reviewing data.

Software Advances

In the past, growers have been discouraged from adopting potato yield monitoring because the analytic software was complicated and not user-friendly. That is not the case today. Yield data files are basically spreadsheets and the data is simple and ready to use.

The software converts this data into clear, easy-to-read maps and reports, which farmers or agronomists can use to make agronomic decisions. Even if they aren’t currently using the data, both Paget and Menkveld encourage growers to collect the data as they may need it in the future.

Almost all agronomists and crop input specialists can accept yield monitor data, says Menkveld, and will happily work with growers and their data to improve crop productivity.

Software can now make comparisons of yield data from multiple crop types. This is something Paget finds particularly useful. “When I look at my farm, I can see its whole history. Potatoes this year, all the spray records, everything we put into it. I can go back to the 2018 crop when I harvested corn, soybeans or grain, or to 2017 and find all of that information.”

Paget says it’s the initial set-up that may stop growers from monitoring yields.

“The biggest thing is guys are hesitant of setting it all up. It takes time. My wife has been working on it steadily. Now we’re to a point where everything is there. It’s just a matter of checking data and tweaking little things. The initial hard part’s already done,” he says.

Before beginning to collect any data in-season, Paget recommends growers set up GPS displays correctly. “You want your fields named properly, so it’s easier for the operator to change fields.”

Yield data provides instant results, but those results year over year keep providing more in-depth information to growers.

“You can benefit from a yield map immediately. You can look at a yield map after one year and understand what’s happening in your field much better than if you did not have that yield map. What you do with the data and understanding the importance of the data, and what the data is telling you, that process is for years. The value comes in repeating the process,” says Menkveld.

Equipment companies have developed technology that will automatically upload data to a cloud platform where it can be processed later for more intensive investigation of the numbers for comparing yield maps year to year and from one crop to another in the same field. Overlaying these maps helps growers understand production and yield differences from one season to the next, and how their crop management is affecting yield.

In the winter, Paget makes a point of going through all the reports and maps generated during the growing season. Reviewing the data for 40-odd fields is time consuming, says Paget, and in future he may hand this task to a professional, who can compile maps, reports and prescriptions for his crops.

Menkveld also recommends if growers feel they don’t have the time or knowledge to get the best information from the data, that they hire an agronomist or someone specialized in doing that job.

Paget says it’s important to be completely committed to the technology and collecting data. He’s currently set up to keep all records and data in one system, which has been a successful platform for him and other growers he knows.

“They’re doing their planning, spray records, soil analysis, et cetera, in one system, and this yield monitor is just another part — it finishes the system. That’s the way it works for me, too,” says Paget. “When we would go through the fields every year, we would say ‘that’s a poor spot’ and we would never know how much or why. But with a yield monitor you can pick that exact zone out and you can find out why.”