How to save your potato crop from pink eye in the field.

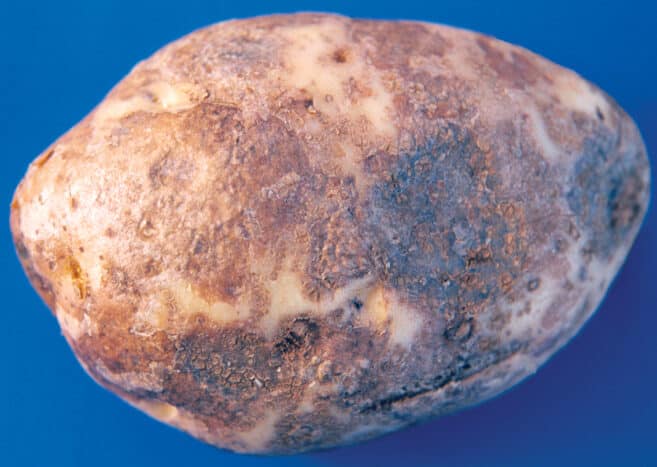

Pink eye is a sporadic disorder of potato tubers that may result in a significant loss of quality after harvest. The usual symptoms are pink or light brown, slightly raised areas that are easy to see on moist, freshly dug tubers but difficult to find on dry, unwashed potatoes. The affected areas usually occur around the eyes and at the bud end of the tuber. Severe pink eye affects the tuber flesh, reddish-brown decay extends two to three millimetres into the flesh. The rot may be confused with late blight, but the tuber rot caused by late blight is usually granular and deeper. If tubers are kept cool and dry, the only symptom commonly noticed is scaly, flaky skin over the affected areas. Under extreme conditions, the skin develops corky areas before or after harvest, which make the tubers unmarketable for either fresh market or processing. Pink eye may also cause skin cracks when the lesions dry out. This disorder is usually associated with warm, wet soils at harvest, with non-rotated fields and with Verticillium wilt.

Ed Lulai, a renowned potato physiologist with the United States Department of Agriculture, suggested replacing the name pink eye with “Periderm Disorder Syndrome” (PDS). The pinkish skin colour is short lived, not causal and often not present. Pink eye may also be found on the tuber surface, not only around the eyes, so the name is misleading. Lulai’s studies are consistent with previous findings which show PDS is due to the death of actively dividing skin cells. The cells around the dead areas start to divide and expand, but the resulting divisions are disorderly. Dead cells no longer act as a barrier to tuber infection and dehydration, which results in storage problems such as soft rot or corky lesions.

An easy test for PDS is to put tubers under UV light. The affected areas will fluoresce blue due to the accumulation of suberin compounds in areas of disorderly skin growth.

Growers have no control over the high temperatures and the heavy rains that promote pink eye. However, there are things growers can do. The best management strategies are:

- Practice crop rotation — It helps to increase organic matter an important component of soil health.

- Manage Verticillium early dying — Early dying reduces canopy coverage and loss of canopy allows soils to warm faster on sunny days, thus leading to higher temperatures that are more favourable for pink eye development. In fields with a history of Verticillium, do not plant varieties susceptible to pink eye such as Superior, Kennebec, Shepody, Yukon Gold and Pike.

- Reduce soil compaction — Compaction results in poor drainage that increases susceptibility to tuber diseases and disorders. To minimize wet soils, deep till areas where water tends to collect and areas where soils are usually compacted (e.g., field entrances or head lands). Deep tillage will open up the subsoil that may be impeding proper drainage during wet weather. Improved drainage will limit periods when tubers will be oxygen deprived and thus more prone to pink eye. Also, avoid using heavy machinery when soils are wet. Minimizing water-saturated soils won’t only reduce the likelihood of pink eye but will also help limit the development of other tuber diseases or disorders

- Keep available soil moisture below 95 per cent during tuber maturation — This is tricky; soil moisture shouldn’t be depleted too much because desiccated tubers are susceptible to blackspot bruising during harvest.

- Test digging — Do test digs before harvest to identify areas with high incidence of pink eye.

- Check low spots, wet areas, and compacted areas in particular — If symptoms are minor, tubers may still be marketable. If pink eye symptoms are severe, tubers will be rejected and should not be stored. Tubers with pink eye are more vulnerable to soft rot in storage.

There are good and bad pink eye years, just try to do what you can to avoid a bad year.

Header photo — A potato infected with pink rot harvested with pink, puffy lesions. Photo: Eugenia Banks

Related Articles

Top Contenders for Potato Pests and Diseases Across Canada for 2022