Amid growing concern about the discovery of cancer-causing chemicals in potato chips and french fries, a young scientist at the University of Brussels has developed a new laser system that scans peeled potatoes in the factory to detect toxic compounds and prevent them from reaching the consumer.

At present, raw potatoes that produce an excess of the carcinogenic chemical acrylamide cannot be detected in a fast, sensitive and non-destructive way. This new technique, developed by Lien Smeesters with the B-PHOT Brussels Photonics Team at the University of Brussels, in collaboration with Tomra Sorting Solutions, employs a new sensor that scans peeled potatoes, weeding out food that may cause high levels of the toxic chemical.

Currently only general quality tests are available for assessing potatoes with no accurate acrylamide detection. Food safety measures involve a person examining a sample and accepting an entire batch if the small selection passes.

“When frying potatoes, acrylamide formation is one of the biggest concerns of the potato-processing agriculture industry. At present raw potatoes that produce an excess of acrylamide cannot be detected in a fast, sensitive and non-destructive way,” said Smeesters.

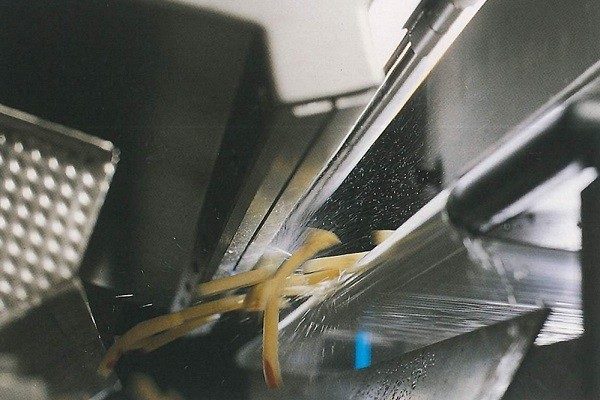

However, with this new sensor, every potato or individual french fry can be examined in a rapid, safe and thorough manner for the first time. It works by scanning the “free falling” food items, such as potatoes, from both the front and back with a laser that employs “spatially resolved spectroscopy,” a non-invasive imaging technique using infrared light. When the laser beam hits a potato, part of the light will be internally scattered during interaction with the tissue. A bad potato produces a deviating internal scattering signal, owing to the high acrylamide precursors, and therefore the system can recognize a “fingerprint” of the undesirable food. This unwanted food item is spotted in mid-air as it begins to fall. Selected by the internal processor, the potato is then “knocked out” of the batch by being blasted with a stream of air and into a reject bin before it hits the conveyor belt below.

The sensor is able to do this with each and every individual potato scanning and rejecting in tiny fractions of a second.

Dr Smeesters explains: “Not all potatoes result in excessive acrylamide formation during frying. We have sought to spot the undesirable potatoes when they are in their raw, peeled stage. After scanning with laser beams, the good potatoes will emit a different light signal than the unsuited ones leading to an unambiguous detection.”

Having filed a patent describing the use of this detection method, the laser scanner will be integrated into one of Tomra’s industrial in-line sorting machines, detecting and discarding food items that may contain excessive acrylamide precursors. Several tons of products could be examined per hour to look for these carcinogenic compounds without using dyes or chemical additives, and without damaging or even touching the food.

Smeesters sees the future benefits of this sensor being more widely available to users in the kitchen: “Although we are a long way off this yet, the miniaturization of the technology would enable a compact potato quality test tool in your home. A hand-held device indicating whether a potato would be unsuited for frying could reduce our exposure to acrylamide.”