[deck]Three Canadian potato experts share their views on the best ways to tackle the disease.[/deck]

It has likely been around for as long as people have been growing potatoes, but researchers are still trying to determine why the pathogen is much more common in some fields than others and what the best methods are for combatting common scab.

While growers are using a number of different practices to try to control the disease, none of them have proven to be totally effective. In this edition of Roundtable, three potato industry experts — Khalil Al-Mughrabi, a pathologist for the Potato Development Centre at New Brunswick’s Department of Agriculture, Aquaculture and Fisheries; Robert Coffin, a prominent private potato breeder in Trenton, Ont.; and Eugenia Banks, a potato specialist with the Ontario Potato Board — weigh in on common scab management practices offering the best chances for success.

Priority Disease

Al-Mughrabi has participated in numerous studies on common scab management practices which include the use of biopesticides, fungicides, soil additives and soil fumigants, as well as experimental measures such as the use of compost and compost tea and a chemical compound extracted from quinoa seeds.

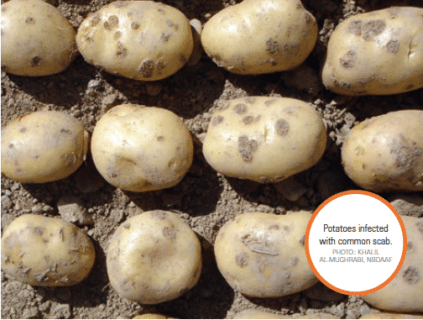

Al-Mughrabi says that common scab is an economically important disease of potato not just in Canada, but around the world. Infected tubers show superficial, raised, or deep-pitted brownish lesions, which ultimately reduce the quality and marketability of both fresh market and processing potatoes.

“Common scab has been identified by stakeholders across Canada as a priority disease for which adequate control measures are lacking,” he says, adding the disease is most prevalent in Eastern Canada.

Al-Mughrabi says common scab is known to be caused by the pathogen Streptomyces scabies, but other less common pathogenic species of Streptomyces may also be involved.

“There are hundreds of bacterial species in the Streptomyces genus that seem to be found in most soils. This could explain why a potato cultivar may not be affected by common scab in one area, but have severe scab when planted in another area,” he says.

According to Al-Mughrabi, common scab is almost always transmitted to fields through infected seed pieces, although it can also be spread by spores in the soil, in soil water and possibly on nematodes or insects. Once the disease is established in a field, the scab pathogen will survive on infected crop residue buried in the soil even under harsh environmental conditions, making it very difficult to eradicate or manage.

In many areas of Canada and the United States, soil fumigants such as chloropicrin are routinely used to treat scab infections in processing and table potatoes. Al-Mughrabi says some growers use fumigation in an effort to control potato diseases like early dying, but fumigants have also been shown to reduce common scab, Rhizoctonia and a number of other soil pathogens.

Al-Mughrabi says that biopesticides have also been shown to suppress common scab, referring to a recent study which reported a biopesticide containing Bacillus subtilis reduced common scab by 56 per cent.

Al-Mughrabi offers the following suggestions for growers looking for ways to manage common scab in their fields.

CLEAN SEED

Plant clean, certified, disease-free seed.

CHEMICAL CONTROL

A broad-spectrum chemical seed piece treatment may provide some control. For example, a recent study reported that fludioxonil reduced common scab by 58 per cent. However, chemical treatments are no substitute for clean, disease-free seed.

RESISTANT VARIETIES

Planting scab-resistant potatoes can be one of the best options, if the cultivar fits the potato operation. However, no varieties are completely immune to common scab. Avon, Cherokee, Chieftain, Hilite Russet, Huron and Wauseon are all considered highly resistant varieties.

COVER CROPS

Growing cover crops such as mustard can be useful. Mustard acts as a biofumigant that can potentially control various soil pathogens, as long as it is handled correctly (mustard has to be chopped and mixed into moist soil in order to be effective).

CROP ROTATION

A three- to five-year rotation of crops is important, as continuous cropping of potatoes in problem fields can lead to increased disease severity. Non-host crops like alfalfa, rye and soybeans are considered good rotational choices. Plowing down legumes or red clover may encourage common scab development.

ORGANIC MATTER

Crop rotations and soil management practices that favour the increase of soil organic matter can be used to maintain soil moisture during tuber development. The activity of the common scab organism is known to be inhibited in moist soils.

SOIL MOISTURE

If available, irrigation at tuber set (4 – 6 weeks after planting) can help maintain adequate soil moisture. It’s been reported that increasing soil moisture to 80 – 85 per cent during tuber initiation until tubers are 1-1.5 inches in size can reduce common scab incidence.

SOIL PH

Common scab is most common in soils with pH 5.5 – 7.5, so as a general rule it’s advisable to avoid liming to a point where the soil pH exceeds 5.4. Disease incidence may be reduced by applying acid-forming fertilizers such as ammonium sulphate, which can lower soil pH. Similarly, if soil calcium is required, gypsum can be applied without raising soil pH. Manganese may lower scab incidence without elevating soil pH. However, lowering the soil pH may affect the choice of rotation crops and can alter the availability of certain soil nutrients.

SOIL ADDITIVES/AMENDMENTS

Applying large amounts of farmyard manure in problem fields should be avoided, as this will provide a food base for the common scab organism. Applying mustard meal and saponins extracted from Chenopodium quinoa can reduce common scab incidence and increase marketable yield.

Al-Mughrabi maintains an integrated approach that combines different management methods is better than relying on a single practice.

“Chemical control is not sustainable as pathogens can develop resistance to them very quickly,” he says, adding that using a resistant variety is a good management tool but it may not be an option if it doesn’t fit a potato operation and the types of varieties required by some end-users.

“Cultural practices such as crop rotation, soil pH, water management, and incorporating biofumigants [like] mustard will aid in the success of disease management. This way if one approach fails to achieve control, other approaches will help,” says Al-Mughrabi.

Infested Fields

Robert Coffin and his wife, Joyce Coffin, are long-time Prince Edward Island potato breeders, but in November the couple decided to pull up stakes and start a new breeding business in Trenton, Ont. The Coffins have a lot of experience dealing with common scab because their potato fields at Privar Farm in North Wiltshire, P.E.I., were rife with the disease.

Coffin says he and his wife started their first potato breeding operation on the Island on dairy farm land that had been farmed for 200 years.

“We had no problems with scab there. Then we shifted our farm operation to another location in Prince Edward Island where we cleared land out of the forest, and we were totally surprised to see we had serious scab [problems],” he says.

“The thing that told us right off the top was that you don’t necessarily have to have a previous history of potato production in order to have scab. The organism can already be there.”

Coffin says he tried a number of cultural practices including different crop rotations to try to get the common scab under control without much success.

“There are some certain crop rotations that have been suggested might help. But on our farm, we tried a number of different crops, including oilseed radish, oats, barley, clover, winter rye and hot mustard, and it didn’t seem to have any effect on the severity of the scab,” he says. “It was there just year after year.”

Coffin says if his crop rotation trials had taken place on land that wasn’t under severe common scab pressure, the results may have been different. “If scab pressure is only moderate, you might see some improvements,” he says.

A few years ago, Privar Farm participated in a study that evaluated a product containing several types of bacteria and its efficacy in suppressing common scab. In the first year, Coffin says, the biopesticide, which was applied in-furrow at planting, exhibited good control but in two subsequent years of trials the results were inconsistent.

Coffin believes at the present time, planting resistant varieties and soil fumigation probably provide the best defence for growers against common scab.

“We know that some varieties of potatoes have a fair amount of field resistance to scab,” he says. “But at the same time, some of the ones that have the best resistance to scab may not have really desirable agronomic traits such as yield or processing quality. So that’s the problem.”

Coffin says soil fumigation isn’t an option for potato farms in Prince Edward Island, where the use of fumigants have been banned since 2002 due to concerns over water quality. He also points out fumigation is an expensive solution and is only temporary, since fields can revert back to their original population of living organisms — which can include common scab pathogens — within a few years.

“Soil fumigation is not a permanent fix,” Coffin says. “I think that’s important to recognize.”

Genetic Resistance

Eugenia Banks has conducted numerous studies on common scab control and also delivered presentations on the topic at potato conferences in both Canada and the United States.

The potato specialist with the Ontario Potato Board says field trials have shown registered seed treatments have little if any effect on common scab bacteria. Additionally, fumigation with chloropicrin has been shown to produce inconsistent results.

“It may reduce scab incidence in some fields but not in others,” she says.

Banks says because common scab bacterium can likely survive indefinitely in the soil in the absence of potatoes, even an eight-year rotation has been shown to be ineffective as a control measure.

She points out that practices such as liming or spreading contaminated cattle manure on fields can favour the development of common scab.

Banks says growers can avoid introducing the common scab pathogen in their fields by planting healthy seed. She adds, however, even healthy-looking seed can carry the scab bacterium on the skin or in the lenticels.

Side-dressing with fertilizers containing sulfur like ammonium sulfate, she says, has been reported to reduce common scab severity.

Banks maintains “stable genetic resistance” is the most reliable and cost-effective strategy for managing common scab.

“Susceptible varieties such as Yukon Gold, Vivaldi, Chaleur, to name just a few, should be grown only in common scab-free soil. Varieties that are resistant or tolerant to scab like Pike, Superior, Gold Rush and Norland should be the preferred varieties in infested fields,” Banks says. However, scab-resistant varieties are not available for all markets and in all growing areas.

SEPARATING SPECIES

A two-year research project on common scab in potatoes that’s supported by the Ontario Potato Board is now in its second year. The project, according to Eugenia Banks, a potato specialist with the board, has already yielded an important breakthrough.

The finding from the first year of study is Streptomyces stelliscabiei is the most common species of common scab in Ontario — not S. scabiei as expected. Banks says this could lead to the development of common scab management practices that specifically target S. stelliscabiei.

“This is a significant finding because methods used to reduce common scab in other potato-growing areas may not work in Ontario,” she says.

According to Banks, the majority of Streptomyces species found in agricultural soils do not cause common scab and only those species which produce a toxin called thaxtomin are pathogenic.

The 2018 research involved collecting 50 soil samples from potato fields in different parts of Ontario. A type of molecular analysis called polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing conducted by A&L Canada Laboratories revealed 48 of the fields tested positive for the presence of thaxtomin-producing Streptomyces species and that most of them contained multiple species.

In addition to S. stelliscabiei and S. scabiei, two other pathogenic Streptomyces species — S. turgidiscabiei and S. acidiscabiei — were identified in the soil tests.

Banks says A&L Canada Laboratories will offer this testing service to Ontario growers with problem fields who want to find out which species of pathogenic Streptomyces are present.

The study could assist in the development of custom-tailored approaches to common scab control by adjusting management practices to the kind of bacteria found in individual fields, she says.

The soil tests showed there was a correlation between how much common scab bacteria is present and nutrient levels within a field. It also helped identify a number of factors such as soil fertility that could help predict levels of common scab in Ontario potato fields.

“This study provides important information to conduct field studies investigating the correlation between macro and micro nutrients and the pathogenic Streptomyces species present in a field,” Banks says.

“The next step will be to determine if changing soil fertility results in changes in the bacteria present and reduces scab levels. The approach will depend on the species of Streptomyces present,” she adds.

“For instance, increasing organic matter in a field infested mainly with S. stelliscabiei should result in a reduction of the population of this Streptomyces species.”

In 2019, the focus of the research project, which is funded in part by the Canadian Agricultural Partnership, will be on assessing the effectiveness of biopesticides on controlling S. stelliscabiei.

Banks says as part of the project, she will also continue research she initiated several years ago on the use of horseradish as a soil amendment to combat common scab.

“I hope to incorporate macerated horseradish roots in a field infested mainly with S. stelliscabiei,” she says, adding that results should be available immediately after the field research is completed and the data it produces is analyzed.