[deck]A detective story about an unusual strain of an uncommon potato pathogen.[/deck]

When alfalfa mosaic virus (AMV) happens to occur in potatoes, it usually causes leaf mottling and blotching. Now, researchers have identified an unusual strain that causes necrosis – brownish dead patches – in tubers, the first such AMV strain found in Canada.

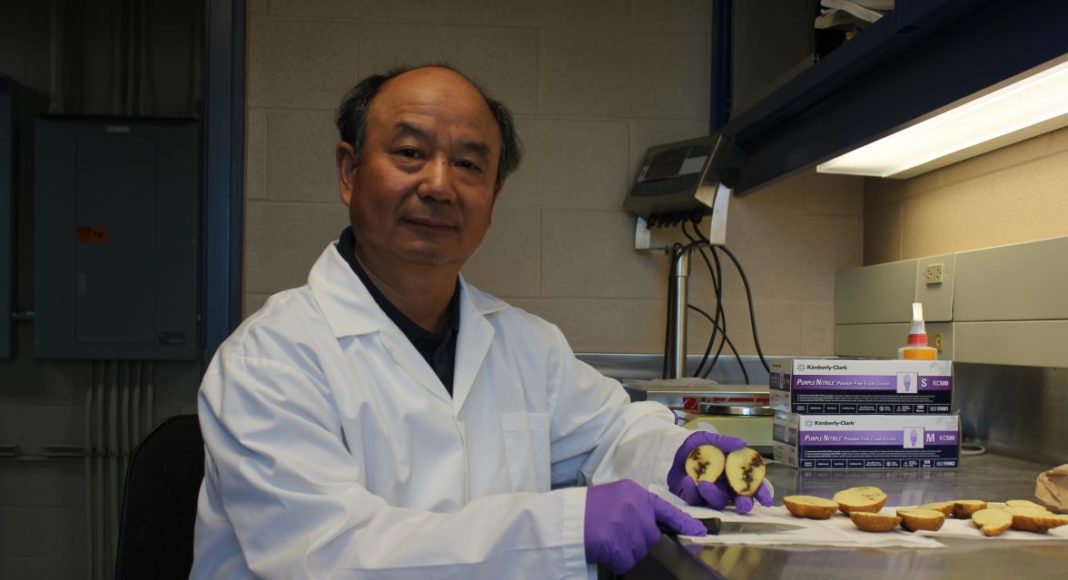

The story of how this tuber-necrosis culprit was identified is a little like something from CSI: Crime Scene Investigation. The infected tubers were discovered in 2012 during routine sampling in a commercial field. That finding was quite surprising because the cultivar involved doesn’t normally show internal tuber symptoms in response to the pathogens normally encountered in the region. So the tubers were sent to Xianzhou Nie, a research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Fredericton, to find out what had caused the problem.

“We got a few tubers showing extensive internal necrosis. We subjected this material to laboratory tests for 10 different viruses. We found PVS [Potato virus S] and PVY [Potato virus Y],” says Nie. “Then we did further analysis to see which strain of PVY we were dealing with. We identified it as PVYNTN.” PVYNTN (tuber necrosis strain) causes brownish necrotic rings in the tubers of susceptible varieties, so it was a possible suspect.

But was the necrosis actually caused by a virus or by some other type of pathogen? To check out that possibility, Nie’s research team planted the tubers in a greenhouse. “The plants showed a lot of virus-like symptoms, like mosaic on the leaves, so we were fairly confident that it was a viral problem. Moreover, the tubers from these daughter plants also showed very strong internal necrosis,” he says.

“So we thought we might be dealing with PVYNTN alone or in combination with PVS. So we inoculated a virus-free sample of the same cultivar with different strains of PVY alone or in combination with PVS. But interestingly, none of the strains caused any necrosis at all.”

Their next step was to test the original material using a new technology called next generation sequencing, which can detect small virus-derived genetic material (ribonucleic acid, RNA). Nie says, “We found PVS and PVY, of course, but we also found alfalfa mosaic virus. And we knew that certain strains of alfalfa mosaic virus could induce necrosis on potato tubers.”

To figure out if this unexpected suspect was the true culprit, the researchers first had to separate AMV from PVYNTN and PVS. To do that, they inoculated the viral material into tobacco, which is immune to PVS, so only AMV and PVYNTN would be produced. Then they inoculated the resulting viral material into a PVY-resistant potato breeding line to get rid of the PVY. They tested the purified viral material to make sure it contained only AMV.

Next, they inoculated the AMV alone or in combination with PVYNTN into a virus-free sample of the original cultivar and compared that with PVYNTN alone as a control. “We found that only those plants inoculated with AMV alone or in combination with PVYNTN had necrosis in the tubers. With PVYNTN alone, the tuber doesn’t have necrosis at all,” notes Nie. So the AMV strain was the culprit.

AMV BASICS

Alfalfa mosaic virus typically causes calico symptoms, bright yellow blotching on the leaves of susceptible potato cultivars. Previous research has found that AMV can be transmitted by 16 aphid species and also through potato pollen and true seed.

“Alfalfa mosaic virus has a very wide host range,” Nie says. “The literature says that in the natural environment the pathogen can infect around 150 plant species; alfalfa is one of the major hosts. Under inoculation conditions, you can infect more than 400 plant species.” Where AMV causes problems in potatoes, it tends to be found on the edges of potato fields growing near alfalfa or clover.

“[In Canada] alfalfa mosaic virus occasionally causes some calico-like symptoms in potatoes, but it is not a major issue,” he says. In an earlier study, Jingbai Nie and Huimin Xu, who are both with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, collected leaf samples with calico symptoms from several provinces in 2003 and 2004. They detected AMV in eight isolates from Ontario, Alberta and New Brunswick. No tuber necrosis was associated with AMV in any of the sampled cultivars or in Russet Burbank, the cultivar used in the study’s inoculation tests.

The very first identification of an AMV strain causing tuber necrosis was by J.W. Oswald in 1950; the isolate was found in some potatoes in 1946 in California. Tuber-necrosis AMV has not become a common problem since then.

So far, the tuber-necrosis strain of AMV found in New Brunswick seems to be an isolated case; Nie has not heard of any other cases from people working in the field. He and his colleagues are doing some follow-up work to learn more about this strain, such as determining how similar or different it is compared to other AMV strains found in Canada, and whether it causes tuber necrosis in other cultivars.

Nie concludes, “Although the alfalfa mosaic virus necrosis strain appears to be scary, the virus’s overall occurrence is low so there is no need to panic. Nevertheless we still recommend that growers follow the general recommendations in terms of virus management such as using clean seeds, roguing and all those good practices.”

VIRUS MANAGEMENT TIPS FOR GROWERS

Although management of some specific potato viruses may require particular measures, Khalil Al-Mughrabi, potato pathologist with the New Brunswick Department of Agriculture, Aquaculture and Fisheries, outlines several overall recommendations:

- Use certified and disease-free seed tubers

- Use resistant varieties, if available

- Remove visibly diseased plants from the field as soon as possible (roguing)

- Control volunteer plants from the previous season

For aphid-transmitted viruses, he advises, “Plant early to avoid heavy aphid populations. Check current local recommendations for aphid catches (thresholds) and administer chemical aphid control accordingly. Chemical control is not always completely effective [in some situations], as the aphids may infect many plants before the insecticide is able to kill them. An oil spray should be used to prevent aphids from transmitting the virus while they feed.” If AMV is an issue, growers should avoid planting potatoes near alfalfa or clover.

For tuber-transmitted viruses, Al-Mughrabi recommends, “Avoid unnecessary handling of plants, and avoid contact between disease-free tubers and those that are potentially carrying the disease. Ensure that hand tools are cleaned frequently while working, and that equipment is cleaned thoroughly between different lots and fields.”