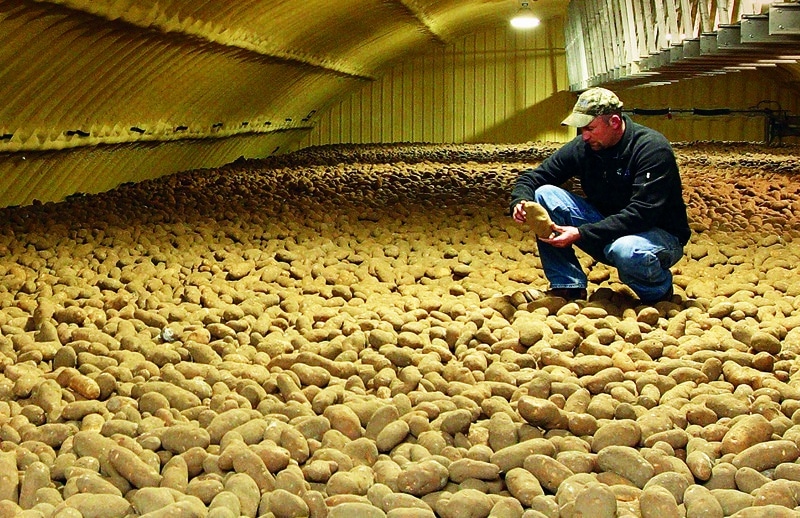

In Idaho, potatoes are both a humble stereotype and a half-billion dollar crop. According to the Idaho Farm Bureau Federation, every spring farmers plant more than 320,000 acres of potatoes valued at between $550-$700 million. Yet unbeknownst to most consumers, roughly 30 per cent of the potatoes harvested spoil before they reach a grocery store shelf.

Boise State University researchers Harish Subbaraman, David Estrada and Yantian Hou hope to change that. In a recently awarded one-year $413,681 Idaho Global Entrepreneurial Mission (IGEM) grant, Boise State is collaborating with Idaho State University and industry partners Isaacs Hydropermutation Technologies, Inc (IHT) and Emerson to develop a wireless sensor network that would be able to detect temperature, humidity levels, and carbon dioxide and ammonia levels in real time, to help with early detection of rot.

The cloud-enabled sensor system will feature three-dimensional hot spot visualization and help predict oncoming rot or deteriorating quality of stored potatoes. This will allow owners to use the real-time sensor data, along with a miniature air scrubber system IHT is developing, to respond to potential problems quickly, as they develop.

“The current problem is, there are no sensors that can do early detection of rot,” says Harish Subbaraman, assistant professor electrical engineering at Boise State University. “But if you can identify rot at an early stage, you can prevent crop loss on a large scale.”

According to David Estrada, assistant professor Materials Science at Boise State, rot spreads on contact. “The way the system works now is, a farmer walks into their facility, smells rotten potatoes and that’s it. But our sensors can detect parts per million, or even parts per billion, and can tell us in exactly which bin the sensor is detecting rot. That way, farmers can go out, pull out a few rotten potatoes and save the rest of the batch.”

Estrada explained that the cost of printing sensors could be as low as a few dollars apiece. Not only would the monitoring system hopefully prevent waste, it could help preserve the quality of potatoes in the facility.

Subbaraman and Estrada plan to have their sensors tested in a facility by the end of their year-long grant cycle by working with industry partner Emerson PakSense. But Estrada points out that this project has been three years in the making and will continue long past the IGEM grant.

Source: PotatoPro